A disclaimer: this article is merely information about what laws exist. It does not constitute advice. Read, research, research further, and come to your own conclusions.

That being said, a request in Ontario had been made asking about was on the books regarding forced (or coerced) tests. This is course refers to the nasal rape sticks that are being passed off as coronavirus tests. Here is what some digging uncovered. Again, take this as information, and then decide for yourself.

On the issue of masks as a human rights issue, recent Clown Rights Tribunals have found that these demands from stores can be enforced in most cases. Simply having breathing issues is not sufficient. How it would be enforced in a health care setting is a bit more complicated. That said, let’s take a look at the poking stuff.

https://www.cpso.on.ca/About/Legislation-By-Laws

https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/930856

https://www.cpso.on.ca/Physicians/Policies-Guidance/Policies/Consent-to-Treatment/Advice-to-the-Profession-Consent-to-Treatment

https://www.canlii.org/en/on/laws/stat/so-1996-c-2-sch-a/latest/so-1996-c-2-sch-a.html

https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/page-51.html#docCont

https://www.laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/F-27/page-8.html#h-234517

Interim Order From Patty Hajdu

- Know What Is Actually Considered Malpractice

- Understand What Consent Really Is

- Applicable Legislation: Health Care Consent Act, 1996

- Canada Criminal Code

- Approved v.s. Interim Authorized Treatments

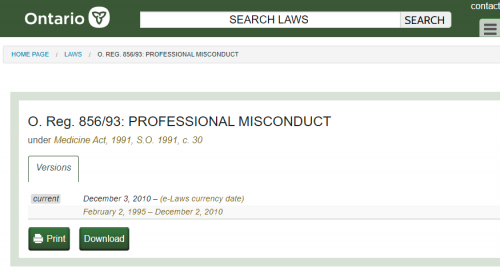

1. How College Of Physicians Views Malpractice

Medicine Act, 1991

Loi de 1991 sur les médecins

ONTARIO REGULATION 856/93

PROFESSIONAL MISCONDUCT

Consolidation Period: From December 3, 2010 to the e-Laws currency date.

Last amendment: 450/10.

This Regulation is made in English only.

.

1. (1) The following are acts of professional misconduct for the purposes of clause 51 (1) (c) of the Health Professions Procedural Code

.

2. Failing to maintain the standard of practice of the profession.

.

3. Abusing a patient verbally or physically.

.

7. Discontinuing professional services that are needed unless,

i. the patient requests the discontinuation,

ii. alternative services are arranged, or

iii. the patient is given a reasonable opportunity to arrange alternative services.

.

8. Failing to fulfil the terms of an agreement for professional services.

.

9. Performing a professional service for which consent is required by law without consent.

.

12. Failing to reveal the exact nature of a secret remedy or treatment used by the member following a proper request to do so.

.

13. Making a misrepresentation respecting a remedy, treatment or device.

.

14. Making a claim respecting the utility of a remedy, treatment, device or procedure other than a claim which can be supported as reasonable professional opinion.

On the College of Physicians and Surgeons for Ontario website, they have a link to a very extensive list of what is considered to be malpractice. On the surface, forcing “Covid tests” would certainly seem to qualify as misconduct on several counts. If a person cannot access health care in a normal fashion without having this pushed on them, it would appear to count as misconduct, at least in Ontario.

Also, #12 makes it very clear that the exact nature of whatever medical procedure must be explained. That includes the process, and the risks. This cannot be shrugged off. Obviously, they will be at a loss to explain how these “Covid tests” or these “vaccines” actually work.

2. CPSO Describes Consent For Treatment

Source of Obligations

What is the source of my consent obligations?

.

Physicians have both legal and professional obligations to obtain consent prior to providing treatment. Although the policy does not contain an exhaustive catalogue, it does highlight many of the legal obligations set out in the Health Care Consent Act, 1996 (HCCA). It also sets out certain obligations that are not codified in the HCCA, but are professional expectations of physicians set by the College.

My patient is refusing to consent to a treatment that I think they should have. Does this mean they are incapable?

.

Not necessarily. Patients and SDMs have the legal right to refuse or withhold consent. Consent can also be withdrawn at any time, by the patient if they are capable with respect to the treatment at the time of the withdrawal, or by the patient’s SDM if the patient is incapable.

.

Patients or SDMs may sometimes make decisions that are contrary to the physician’s treatment advice. You cannot automatically assume that because the patient is making a decision you do not agree with, that they are incapable of making that decision.

.

It is possible, however, that a patient’s decision may cause you to question whether the patient has the capacity to make the decision (e.g., that the patient may not truly understand the consequences of not proceeding with the treatment). Where this is the case, you may want to consider doing a more thorough investigation of the patient’s capacity to ensure the patient’s decision is informed and valid.

.

It is important to remember that it is inappropriate for a physician to end the physician-patient relationship in situations where the patient chooses not to follow the physician’s treatment advice (for more information, see the College’s Ending the Physician-Patient Relationship policy).

The CPSO makes it clear that consent is MANDATORY in order to do anything to the patient. Moreover, it is explicitly stated that it’s considered inappropriate to terminate the patient-physician relationship just because the doctor doesn’t personally agree with the patient’s decision(s).

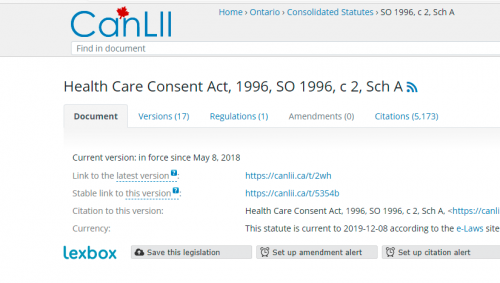

3. Ontario Health Care Consent Act, 1996

Purposes

.

1 The purposes of this Act are,

(a) to provide rules with respect to consent to treatment that apply consistently in all settings;

(b) to facilitate treatment, admission to care facilities, and personal assistance services, for persons lacking the capacity to make decisions about such matters;

(c) to enhance the autonomy of persons for whom treatment is proposed, persons for whom admission to a care facility is proposed and persons who are to receive personal assistance services by,

(i) allowing those who have been found to be incapable to apply to a tribunal for a review of the finding,

(ii) allowing incapable persons to request that a representative of their choice be appointed by the tribunal for the purpose of making decisions on their behalf concerning treatment, admission to a care facility or personal assistance services, and

(iii) requiring that wishes with respect to treatment, admission to a care facility or personal assistance services, expressed by persons while capable and after attaining 16 years of age, be adhered to;

No treatment without consent

.

10 (1) A health practitioner who proposes a treatment for a person shall not administer the treatment, and shall take reasonable steps to ensure that it is not administered, unless,

(a) he or she is of the opinion that the person is capable with respect to the treatment, and the person has given consent; or

(b) he or she is of the opinion that the person is incapable with respect to the treatment, and the person’s substitute decision-maker has given consent on the person’s behalf in accordance with this Act.

Elements of consent

.

11 (1) The following are the elements required for consent to treatment:

1. The consent must relate to the treatment.

2. The consent must be informed.

3. The consent must be given voluntarily.

4. The consent must not be obtained through misrepresentation or fraud.

.

Informed consent

(2) A consent to treatment is informed if, before giving it,

(a) the person received the information about the matters set out in subsection (3) that a reasonable person in the same circumstances would require in order to make a decision about the treatment; and

(b) the person received responses to his or her requests for additional information about those matters

.

Same

(3) The matters referred to in subsection (2) are:

1. The nature of the treatment.

2. The expected benefits of the treatment.

3. The material risks of the treatment.

4. The material side effects of the treatment.

5. Alternative courses of action.

6. The likely consequences of not having the treatment.

The 1996 Health Care Consent Act makes it clear that consent to any medical treatment must be voluntary, informed, and the risks spelled out. These are not things that can just be ignored under the guise of an “emergency”.

For the nasal rape sticks: ask probing questions. Ask what are the effects of putting cotton almost to the brain barrier? Ask if they have verified themselves the sticks are not contaminated in any way. Ask how the PCR test works, and get specific information.

For the gene replacement “vaccines”: ask about the lack of testing on certain groups. Ask about the ongoing testing, and how they can be sure they are safe. Ask if they know and understand what is even in them. This shouldn’t be controversial.

Offences Against the Person and Reputation (continued)

Duties Tending to Preservation of Life (continued)

Marginal note:Duty of persons undertaking acts dangerous to life

4. Canada Criminal Code Provisions

Duty of persons undertaking acts dangerous to life

.

216 Every one who undertakes to administer surgical or medical treatment to another person or to do any other lawful act that may endanger the life of another person is, except in cases of necessity, under a legal duty to have and to use reasonable knowledge, skill and care in so doing.

Duty of persons undertaking acts dangerous to life

Marginal note: Duty of persons undertaking acts

.

217 Every one who undertakes to do an act is under a legal duty to do it if an omission to do the act is or may be dangerous to life.

Duty of persons undertaking acts dangerous to life

Marginal note: Duty of persons directing work

.

217.1 Every one who undertakes, or has the authority, to direct how another person does work or performs a task is under a legal duty to take reasonable steps to prevent bodily harm to that person, or any other person, arising from that work or task.

Criminal negligence

.

219 (1) Every one is criminally negligent who

(a) in doing anything, or

(b) in omitting to do anything that it is his duty to do,

shows wanton or reckless disregard for the lives or safety of other persons.

.

Definition of duty

(2) For the purposes of this section, duty means a duty imposed by law.

Assault

.

265 (1) A person commits an assault when

(a) without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly;

(b) he attempts or threatens, by an act or a gesture, to apply force to another person, if he has, or causes that other person to believe on reasonable grounds that he has, present ability to effect his purpose; or

(c) while openly wearing or carrying a weapon or an imitation thereof, he accosts or impedes another person or begs.

.

Marginal note: Application

.

(2) This section applies to all forms of assault, including sexual assault, sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party or causing bodily harm and aggravated sexual assault.

.

Marginal note: Consent

.

(3) For the purposes of this section, no consent is obtained where the complainant submits or does not resist by reason of

(a) the application of force to the complainant or to a person other than the complainant;

(b) threats or fear of the application of force to the complainant or to a person other than the complainant;

(c) fraud; or

(d) the exercise of authority.

Just a take on this, but could pressuring people to take needles into their arms, or sticks up their nose, be seen as breaching the Criminal Code of Canada? Serious crimes can’t be masked simply by classifying them as medical care.

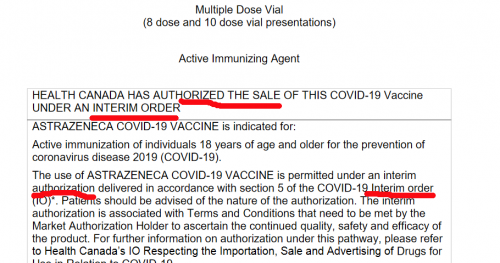

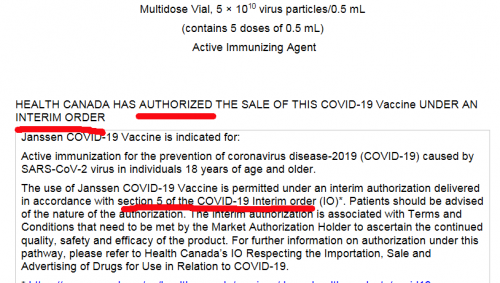

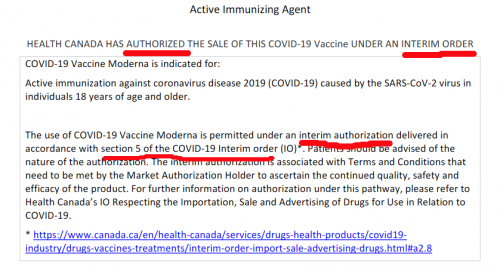

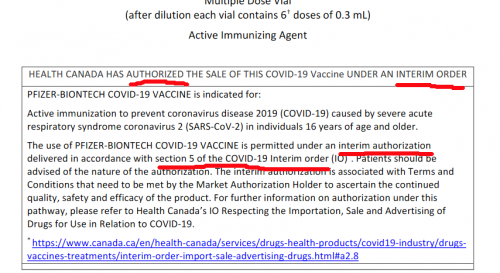

5. Interim Authorization V.S. Approval

To make this point, consider these categories:

(a) Approved: Health Canada has fully reviewed all the testing, and steps have been done, with the final determination that it can be used for the general population

(b) Interim Authorization: deemed to be “worth the risk” under the circumstances, doesn’t have to be fully tested. Allowed under Section 30.1 of the Canada Food & Drug Act, if an Interim Order is signed. Commonly referred to as an emergency use authorization.

https://covid-vaccine.canada.ca/info/pdf/astrazeneca-covid-19-vaccine-pm-en.pdf

https://covid-vaccine.canada.ca/info/pdf/janssen-covid-19-vaccine-pm-en.pdf

https://covid-vaccine.canada.ca/info/pdf/covid-19-vaccine-moderna-pm-en.pdf

https://covid-vaccine.canada.ca/info/pdf/pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-pm1-en.pdf

Here’s a question that even small children should be able to understand: Looking at the product monographs, does it say these “vaccines were approved? Or does it say they were authorized under section 5 of an Interim Order? If the person doesn’t know, (and most won’t), pushing for vaccination would probably be malpractice.

It can’t really be informed consent if the people pushing it have no information about the product in question.

6. No Science Behind Any Of This

Too long to detail here, but there is no real science behind any of this so called “pandemic”. As an example, these “gold-standard” PCR tests are unable to distinguish between dead genetic material and an active infection. Using them at all is fraudulent. Feel free to argue any of this.

Now, just because these protections are in place, it doesn’t mean that health care workers actually know about them. It also doesn’t mean that they will care if push comes to shove.

That being said: at least know what you are talking about when you try to assert your rights. Perhaps bring a recording device if possible. That should make it easier for the patient.

To reiterate from before: all of this content is for informational purposes, and should not be considered professional advice. Please, do your own homework.

Discover more from Canuck Law

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.