Here we go again.

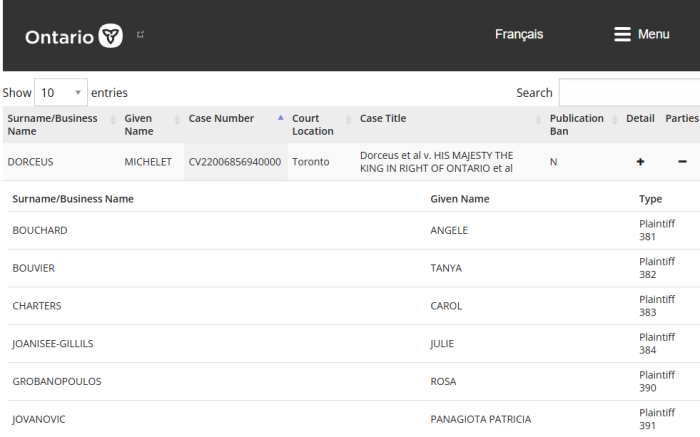

On August 18th, 2024, a Motion for Summary Judgement will be heard in the Civil Branch of the Ontario Superior Court in Toronto. This was over injection mandates dating back to 2021. Approximately 300 healthcare workers — working in many different settings — will see if their case is thrown out.

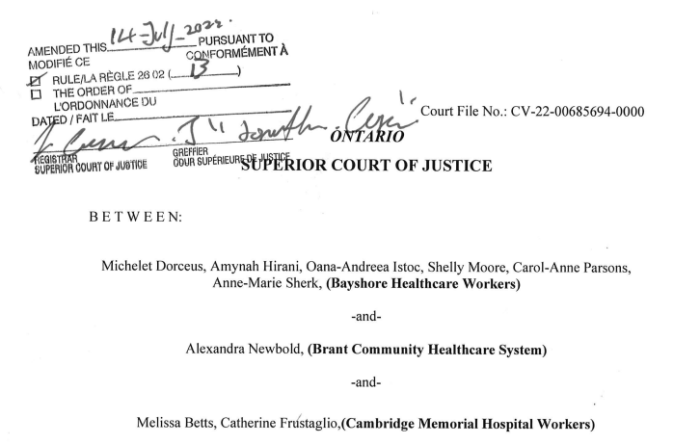

The original Claim was filed in 2022, and an amended one in 2023.

The main reason for this Motion is that the vast majority of Plaintiffs are likely ineligible to sue. Being part of a union typically means that there’s no right to go to Court. Collective agreements usually have a grievance process that ends with arbitration, but doesn’t allow for litigation.

Beyond that, the Statement of Claim is so poorly and incoherently written that it’s likely to be struck anyway. It doesn’t plead any of the necessary information required, and most of what it does include is irrelevant. It appears to have been written by someone with no understanding at all of Civil Procedure.

All that’s missing is a tirade about Bill Gates and microchipping.

This isn’t Vaccine Choice Canada or Action4Canada or Take Action Canada. Nor is it the mess, Adelberg. This is yet another “bad beyond argument” pleading. The main defects are:

- Failure To establish Jurisdiction of the Court

- Failure to seek Relief within Jurisdiction of the Court

- Failure to plead concise set of material facts

- Failure to keep evidence out of Claim

- Failure to remove argument from Claim

- Failure to plead facts which would support conclusions of law

- Failure to give Claim particulars

- Failure to specify who should pay damages

- Failure to properly plead s.2 (fundamental freedoms) Charter breaches

- Failure to properly plead s.6 (mobility rights) Charter breaches

- Failure to properly plead s.7 (security of the person) Charter breaches

- Failure to properly plead s.15 (equality) Charter breaches

- Failure to properly plead tort of intimidation

- Failure to properly plead tort of conspiracy

- Failure to properly plead tort of malfeasance

- Failure to state a Cause of Action

- Failure to appreciate Statute of Limitations

- Claim just a duplicate of other cases

This is just a brief critique, but let’s get into it.

1. Failure To Establish Jurisdiction Of The Court

RULE 21 DETERMINATION OF AN ISSUE BEFORE TRIAL

Where Available

To Any Party on a Question of Law

21.01

To Defendant

(3) A defendant may move before a judge to have an action stayed or dismissed on the ground that,

.

Jurisdiction

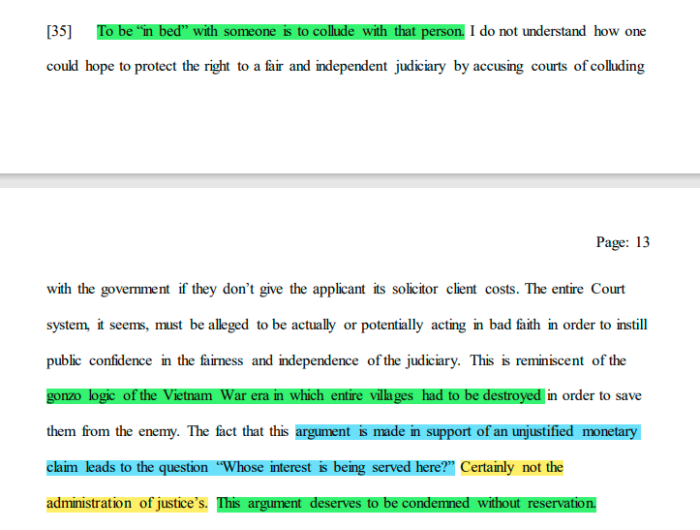

(a) the court has no jurisdiction over the subject matter of the action;

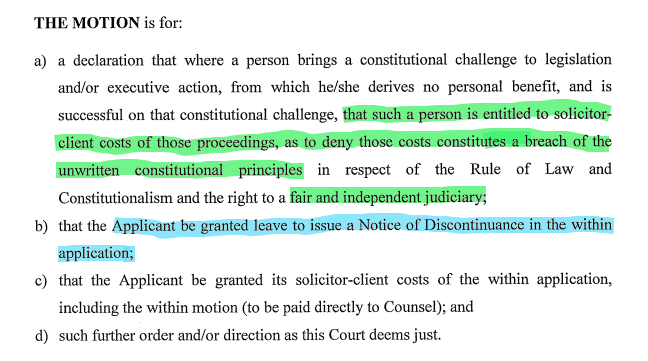

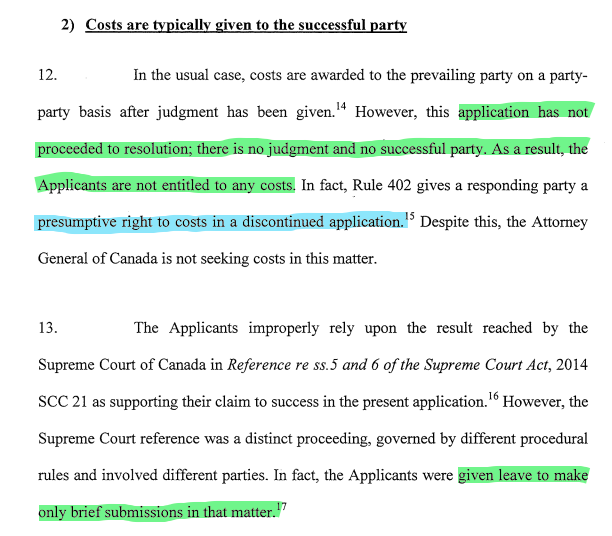

Rule 21.01(3)(a) of Civil Procedure states that a Defendant may move to to have a case stayed or dismissed if there’s no jurisdiction. Why does that matter here? Because the bulk of the Plaintiffs here are from unionized workplaces. Union workers are typically governed by a collective bargaining agreement, and it usually mandates arbitration as a means of settling disputes.

Plenty of cases have already been thrown out for this.

To even (theoretically) overcome this burden, Plaintiffs would have to plead details about what steps they took to resolve this internally. They would have to demonstrate that the process was corrupt or unworkable.

2. Failure To Seek Relief Within Jurisdiction Of The Court

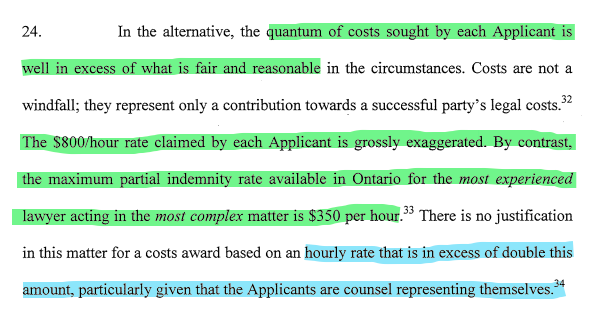

The Relief sought section is downright goofy, and it’s startling to see that an experienced lawyer is including content such as this. It would be bad enough to see an articling student draft such garbage. And it’s not the first time.

- Allegations of criminal conduct

- Allegations of crimes against humanity

- Allegations of eugenics (which would be criminal)

- Allegations of violations of Nuremberg Code

- Allegations of violations of the Helsinki Declaration

Both the Action4Canada and Adelberg (Federal) cases were struck — in part — because they demanded remedies that a Civil Court had no jurisdiction over. Despite being criticized by multiple Courts over this, the same allegations appear here. Mostly likely, this is because this lawyer uses a template and simply cut and pastes from one case to the next.

3. Failure To Plead Concise Set Of Material Facts

Rules of Pleading — Applicable to all Pleadings

Material Facts

.

25.06 (1) Every pleading shall contain a concise statement of the material facts on which the party relies for the claim or defence, but not the evidence by which those facts are to be proved.

In every jurisdiction, Plaintiffs are required to plead the facts. This refers to the: who, what, where, when, and how that things occurred. It is describing a series of events in enough detail that the opposing side — and the Judge — can understand what’s going on.

But that hasn’t happened here. Not a single Plaintiff is described with any detail. Only 8 are even identified in the Claim.

They objected to the injections? What was each one’s specific one?

Who was fired, and who was simply suspended?

Who was required to take the shots, and who was allowed to take the testing?

All Plaintiffs were ineligible for EI? Who applied for it?

None of this is described, nor is the conduct of any Defendant. There are no facts pleaded at all which could possibly be responded to.

4. Failure To Keep Evidence Out Of Claim

The other part of Rule 25.06(1) is that evidence shouldn’t be in a Statement of Claim. The facts are. The facts are simply the sequence of events that each Plaintiff can attest to.

All of the “facts” about the validity of testing and expert views should really be considered expert evidence. That has a place later, but not in the initial pleading.

5. Failure To Remove Argument From Claim

Not only should evidence not be in a Claim, but argument shouldn’t either. The pleading is ripe full of argument, complete with various case citations. However, this is not a Factum, nor a final submission. The original pleading is just supposed to lay out the (alleged) series of events.

How does an experienced lawyer not know this?

6. Failure To Plead Facts To Support Conclusions Of Law

Rules of Pleading — Applicable to all Pleadings

Pleading Law

.

25.06(2) A party may raise any point of law in a pleading, but conclusions of law may be pleaded only if the material facts supporting them are pleaded.

Rule 25.06(2) of Civil Procedure requires that the necessary facts be pleaded in order to support any conclusions of draw that are raised. This makes sense, as there has to be enough meat on the bones to theoretically have the Judge rule favourably. However, there are no facts pleaded about individual Plaintiffs or Defendants, just sweeping declarations without background information.

7. Failure To Give Claim Particulars

Rules of Pleading — Applicable to all Pleadings

Nature of Act or Condition of Mind

.

25.06(8) Where fraud, misrepresentation, breach of trust, malice or intent is alleged, the pleading shall contain full particulars, but knowledge may be alleged as a fact without pleading the circumstances from which it is to be inferred.

Rule 25.06(8) of Civil Procedure states that all pleadings shall have “full particulars”, which is also known as “particularizing a claim”. This is when fraud, misrepresentation, breach of trust, malice or intent is alleged. What this means is that such accusations are made, Plaintiffs have the extra burden to spell out what has happened. All major details must be added.

Quite reasonably, Defendants cannot be left guessing what they have to respond to.

8. Failure To Specify Who Should Pay Damages

Starting on page 33, the money sought is outlined.

- $50,000 for each Plaintiff for “intimidation”

- $100,000 for each Plaintiff for “conspiracy”

- $100,000 for each Plaintiff, by the Government Defendants, for Charter violations

- $200,000 for each Plaintiff for infliction of mental distress and anguish

- $100,000 for each Plaintiff for “punitive damages”

This amounts to $550,000 per Plaintiff, but who exactly is supposed to pay it? It’s specified that the Province is to pay for the Charter violations, but that’s it. If money is to be sought, what is the proposed division? Never mind that none of the torts are properly pleaded, or pleaded at all.

9. Failure To Properly Plead S.2 (Fund. Freedoms) Charter Breaches

However, the Claim doesn’t plead any facts (Rule 25.06(1)) or particulars (Rule 25.06(8)) that would support this. The Claim doesn’t describe how any Plaintiff’s rights to freedom of conscience or belief were violated, nor does it specify which grounds apply to which person.

10. Failure To Properly Plead S.6 (Mobility Rights) Charter Breaches

There are a few mentions — although not properly pleaded — that Plaintiffs had their mobility rights infringed. But there isn’t a single instance of this described. Nor would this be relevant since the travel mandates were Federal, and this case is exclusively Provincial. Most likely, it was cut and pasted from the Adelberg case, which is Federal.

11. Failure To Properly Plead S.7 (Security Of Person) Charter Breaches

Similar to the Section 2 breaches, here, there are no facts (Rule 25.06(1)) or particulars (Rule 25.06(8)) pleaded which would support such allegations. Not a single Plaintiff describes their circumstances. Yes, we assume it to be true initially, but there’s nothing to work with.

12. Failure To Properly Plead S.15 (Equality) Charter Breaches

Section 15 of the Charter isn’t the savior that many think it is. Specifically, “equality” is limited to a fairly small number of groups. None of which apply here, as disappointing as that is.

Enumerated grounds, which are explicitly stated in the Charter, include: race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age or sex.

Analogous grounds, which are additional ones the Courts have endorsed, include: sexual orientation, marital status, off-reserve Aboriginal status and income.

Even if remaining injection-free were an enumerated or analogous ground, there are no facts pleaded which would support the Charter violations anyway. Again, not a single Plaintiff’s circumstances are described in any detail.

13. Failure To Properly Plead Tort Of Intimidation

Because this tort would cover “nature of act or condition of mind”, Rule 25.06(8) requires that full particulars be given, in addition to pleading facts that would support it.

Instead, the Statement of Claim simply states the test, then attempts to argue caselaw in support of it. There are no facts or particulars given — even assuming them to be true — that would support this. Argument is not permitted in this document, anyway.

14. Failure To Properly Plead Tort Of Conspiracy

As with the “intimidation” tort, there are no facts (Rule 26.06(1)) or particulars (Rule 25.06(8)) provided that would support the claim. The document simply states the test and tries to argue.

15. Failure To Properly Plead Tort Of Malfeasance Of Public Office

There are broad, sweeping declarations that the Government Defendants have acted in ways which are contrary to holding public office. But without any facts or particulars, this tort will go nowhere.

The tort of “infliction of mental anguish” isn’t pleaded properly either.

16. Failure To State A Cause Of Action

RULE 21 DETERMINATION OF AN ISSUE BEFORE TRIAL

Where Available

To Any Party on a Question of Law

21.01 (1) A party may move before a judge,

.

(a) for the determination, before trial, of a question of law raised by a pleading in an action where the determination of the question may dispose of all or part of the action, substantially shorten the trial or result in a substantial saving of costs; or

.

(b) to strike out a pleading on the ground that it discloses no reasonable cause of action or defence,

Rule 21.01(1)(b) of Civil Procedure allows Judges to strike a Claim if it discloses no reasonable cause of action. What this means, if there isn’t anything that can realistically be sought, the Court has the power to throw the case out completely, or to allow a rewrite (called granting Leave to Amend).

Here, there are no facts or particulars pleaded to support any of the allegations. The body of the text is argumentative and tries to plead evidence. None of the torts are properly pleaded. A Judge could reasonably conclude that there’s no case to try.

Of course, they tend to allow rewrites, no matter how poorly drafted a case is. Action4Canada was struck with Leave to Amend, which was quite surprising.

17. Failure To Appreciate Statute of Limitations

As many people know, there’s a time limit to file cases. This is commonly referred to as the Statute of Limitations. In Ontario, it’s 2 years for most things, although a number of exceptions exist. See the Ontario Limitations Act.

Even if these Plaintiffs were to hire a competent lawyer (and not withstanding the arbitration requirement), they’d likely be time barred. Since more than 2 years has passed, they wouldn’t be able to include additional claims beyond what’s already there.

18. Claim Just A Duplicate Of Other Cases

A major indicator that clients and donors are being ripped off is that they aren’t getting original work. Instead, it appears that counsel is using a “template” and simply duplicating cases.

Now, if these cases were successful, then it would be a good way to save time and money. But that isn’t at all the situation here.

- Dorceus (this one)

- Katanik (Take Action Canada)

- Adelberg (Federal)

- Sgt. Julie Evans (Police On Guard)

- M.A. and L.A (Children’s Health Defense Canada)

They all kind of look the same, don’t they?

None of them properly pleaded, and none have ever gone anywhere.

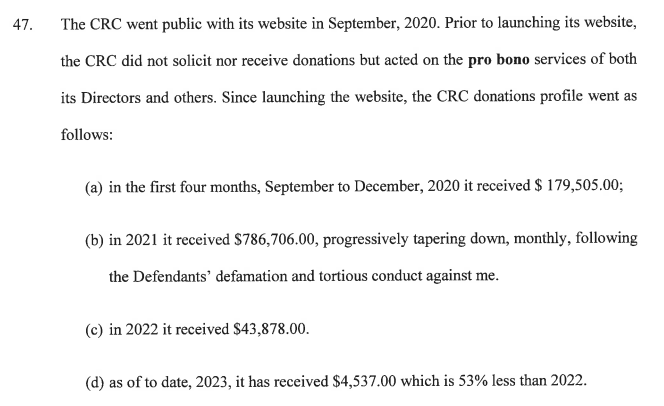

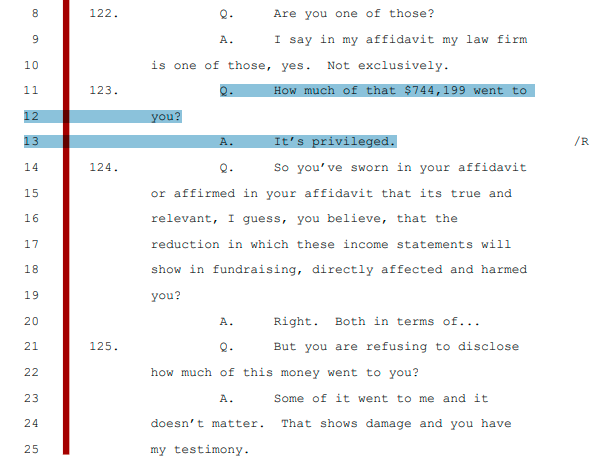

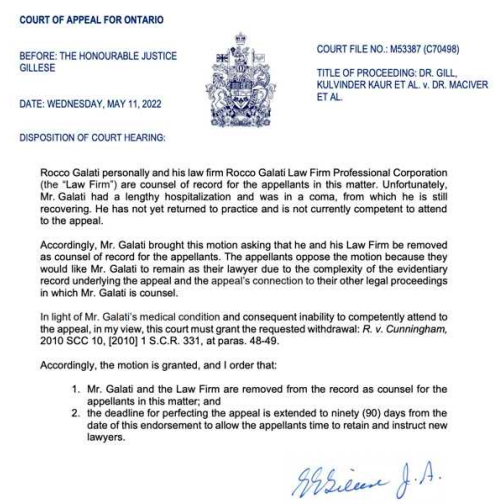

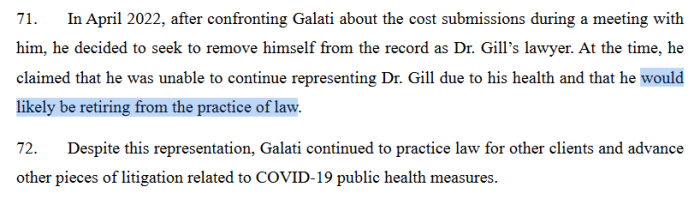

How Many Victims Have Been Ripped Off?

A question that comes up often is how many victims there are of these scam lawsuits. For a partial answer, consider the following:

- 600 – Adelberg (Federal)

- 600 – Federal workers vaccine injury (apparently never filed)

- 300 – Dorceus (this case)

- 100 – Katanik (Take Action Canada’s “First Responders” suit)

These 4 cases alone amount to over 1,600 litigants who have gotten shoddy and mediocre representation. And all from the same lawyer. If one includes all of the donors, it’s no exaggeration to say that there have been several thousand victims who were taken advantage of.

Keep in mind, many, MANY cases have been filed since 2020.

What’s been disappointing is just how little the “independent” media has been speaking up about this. It’s not enough to simply be against lockdowns. Genuine reporters and journalists should be speaking up on behalf of victims who have been taken advantage of with these shoddy lawsuits. There are thousands of clients and donors whose goodwill and desperation have been exploited. They needed a voice.

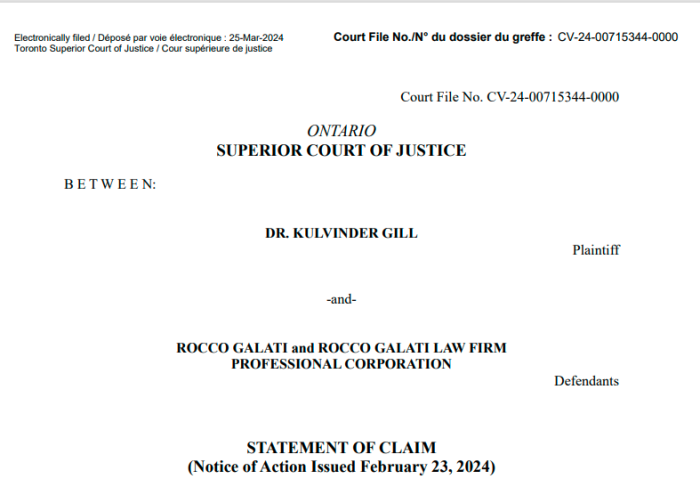

Then of course, some asshole tried in June 2022 to bankrupt a former donor who simply wanted her money back. If this isn’t cause for concern, then what is?

True, it’s a little better now, but more should have been expected. While it’s great to support public interest litigation (overall), we shouldn’t lose track of the people who are really impacted by it.

As for Liberty Talk, perhaps the 25% commission in 2020 clouded her judgement.

(1) Grifters Main Page

(2) https://www.canlii.org/en/on/laws/regu/rro-1990-reg-194/latest

(3) https://www.ontario.ca/page/search-court-cases-online

(4) Dorceus Statement Of Claim

(5) Dorceus Amended Statement Of Claim