(Trudeau announcing new “Digital Charter”)

(New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern at “Christchurch Call”)

Yes, the Christchurch Call and the UN “digital cooperation” are 2 separate initiatives, but the result is the same: stamping out free speech online.

(The UN High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation)

(Liberal ex-Candidate Richard Lee supports UN regulating internet)

1. Important Links

(1) https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/16-05-2019/the-christchurch-call-full-text/

(2) https://globalnews.ca/news/5283178/trudeau-digital-charter/?utm_medium=Twitter&utm_source=%40globalnews

(3) https://canucklaw.ca/unifor-interview-denies-crawling-into-bed-with-government/

(4) https://canucklaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/economic.update.2018.pdf

(5) https://canucklaw.ca/canadian-govt-purges-sunni-shia-from-2019-terrorism-report-bill-c-59/

(6) https://www.blacklocks.ca/feds-to-list-approved-media/

(7) https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-15.html

Interesting UN Links from prior article.

(8) http://www.un.org/en/digital-cooperation-panel/

(9) http://www.un.org/en/pdfs/HLP-on-Digital-Cooperation_Press-Release.pdf

(10) https://digitalcooperation.org/

(11) https://www.cepal.org/cgi-bin/getProd.asp?xml=/socinfo/noticias/noticias/4/48074/P48074.xml&xsl=/socinfo/tpl-i/p1f.xsl&base=/socinfo/tpl-i/top-bottom.xsl

(12) https://www.unescwa.org/sites/www.unescwa.org/files/events/files/program.pdf

(13) https://www.unescwa.org/sub-site/arabDIG

(14) https://www.unescwa.org/publications/internet-governance-challenges-and-opportunities-escwa-member-countries

(15) https://canucklaw.ca/un-wants-to-ban-criticism-of-islam-globally/

2. Text Of Christchurch Call

To that end, we, the Governments, commit to:

.

-Counter the drivers of terrorism and violent extremism by strengthening the resilience and inclusiveness of our societies to enable them to resist terrorist and violent extremist ideologies, including through education, building media literacy to help counter distorted terrorist and violent extremist narratives, and the fight against inequality.

-Ensure effective enforcement of applicable laws that prohibit the production or dissemination of terrorist and violent extremist content, in a manner consistent with the rule of law and international human rights law, including freedom of expression.

-Encourage media outlets to apply ethical standards when depicting terrorist events online, to avoid amplifying terrorist and violent extremist content.

–Support frameworks, such as industry standards, to ensure that reporting on terrorist attacks does not amplify terrorist and violent extremist content, without prejudice to responsible coverage of terrorism and violent extremism. Consider appropriate action to prevent the use of online services to disseminate terrorist and violent extremist content, including through collaborative actions, such as:

-Awareness-raising and capacity-building activities aimed at smaller online service providers;

-Development of industry standards or voluntary frameworks;

-Regulatory or policy measures consistent with a free, open and secure internet and international human rights law.

To that end, we, the online service providers, commit to:

.

-Take transparent, specific measures seeking to prevent the upload of terrorist and violent extremist content and to prevent its dissemination on social media and similar content-sharing services, including its immediate and permanent removal, without prejudice to law enforcement and user appeals requirements, in a manner consistent with human rights and fundamental freedoms. Cooperative measures to achieve these outcomes may include technology development, the expansion and use of shared databases of hashes and URLs, and effective notice and takedown procedures.

-Provide greater transparency in the setting of community standards or terms of service, including by:

Outlining and publishing the consequences of sharing terrorist and violent extremist content;

-Describing policies and putting in place procedures for detecting and removing terrorist and violent extremist content. Enforce those community standards or terms of service in a manner consistent with human rights and fundamental freedoms, including by:

-Prioritising moderation of terrorist and violent extremist content, however identified;

Closing accounts where appropriate;

-Providing an efficient complaints and appeals process for those wishing to contest the removal of their content or a decision to decline the upload of their content.

-Implement immediate, effective measures to mitigate the specific risk that terrorist and violent extremist content is disseminated through livestreaming, including identification of content for real-time review.

-Implement regular and transparent public reporting, in a way that is measurable and supported by clear methodology, on the quantity and nature of terrorist and violent extremist content being detected and removed.

-Review the operation of algorithms and other processes that may drive users towards and/or amplify terrorist and violent extremist content to better understand possible intervention points and to implement changes where this occurs. This may include using algorithms and other processes to redirect users from such content or the promotion of credible, positive alternatives or counter-narratives. This may include building appropriate mechanisms for reporting, designed in a multi-stakeholder process and without compromising trade secrets or the effectiveness of service providers’ practices through unnecessary disclosure.

-Work together to ensure cross-industry efforts are coordinated and robust, for instance by investing in and expanding the GIFCT, and by sharing knowledge and expertise.

-To that end, we, Governments and online service providers, commit to work collectively to:

-Work with civil society to promote community-led efforts to counter violent extremism in all its forms, including through the development and promotion of positive alternatives and counter-messaging.

-Develop effective interventions, based on trusted information sharing about the effects of algorithmic and other processes, to redirect users from terrorist and violent extremist content.

Accelerate research into and development of technical solutions to prevent the upload of and to detect and immediately remove terrorist and violent extremist content online, and share these solutions through open channels, drawing on expertise from academia, researchers, and civil society.

-Support research and academic efforts to better understand, prevent and counter terrorist and violent extremist content online, including both the offline and online impacts of this activity.

-Ensure appropriate cooperation with and among law enforcement agencies for the purposes of investigating and prosecuting illegal online activity in regard to detected and/or removed terrorist and violent extremist content, in a manner consistent with rule of law and human rights protections.

–Support smaller platforms as they build capacity to remove terrorist and violent extremist content, including through sharing technical solutions and relevant databases of hashes or other relevant material, such as the GIFCT shared database.

–Collaborate, and support partner countries, in the development and implementation of best practice in preventing the dissemination of terrorist and violent extremist content online, including through operational coordination and trusted information exchanges in accordance with relevant data protection and privacy rules.

-Develop processes allowing governments and online service providers to respond rapidly, effectively and in a coordinated manner to the dissemination of terrorist or violent extremist content following a terrorist event. This may require the development of a shared crisis protocol and information-sharing processes, in a manner consistent with human rights protections.

–Respect, and for Governments protect, human rights, including by avoiding directly or indirectly contributing to adverse human rights impacts through business activities and addressing such impacts where they occur.

Recognise the important role of civil society in supporting work on the issues and commitments in the Call, including through:

.

-Offering expert advice on implementing the commitments in this Call in a manner consistent with a free, open and secure internet and with international human rights law;

–Working, including with governments and online service providers, to increase transparency;

-Where necessary, working to support users through company appeals and complaints processes.

-Affirm our willingness to continue to work together, in existing fora and relevant organizations, institutions, mechanisms and processes to assist one another and to build momentum and widen support for the Call.

-Develop and support a range of practical, non-duplicative initiatives to ensure that this pledge is delivered.

Acknowledge that governments, online service providers, and civil society may wish to take further cooperative action to address a broader range of harmful online content, such as the actions that will be discussed further during the G7 Biarritz Summit, in the G20, the Aqaba Process, the Five Country Ministerial, and a range of other fora.

Signatories:

Australia

Canada

European Commission

France

Germany

Indonesia

India

Ireland

Italy

Japan

Jordan

The Netherlands

New Zealand

Norway

Senegal

Spain

Sweden

3. Some Observations

Some observations:

- Combatting extremist ideologies and fighting inequality are lumped together.

- This will apparently be done “respecting free speech and human rights”, but aren’t those things already supposed to be protected?

- Parties want to “promot[e] positive alternatives and counter-messaging”. Doesn’t that sound like Onjective 17(c) of the UN Global Migration Compact, promote propaganda positive to migration?

- Encouraging media to use ethical practices when covering violence? And what, shut them down if they refuse?

- Widen support for the call? Collective suicide pact for free speech?

- Looking for expert advice in how to implement “the Call” without violating those pesky free speech and human rights laws. Perhaps you need another Jordan Peterson to make it sound nice and fluffy.

- Research to spot “ROOT CAUSES” of terrorism.

- Look for technical methods to remove terroristic or violent material, (or anything we deem to be violent or terroristic), and share the methods with others.

- Collaborate with partner countries, no real concern of whether they support terrorism themselves, as do many Islamic countries.

- Mess with algorithms to ensure users not directed to “inappropriate content”.

- Regular public reporting, sounds great, except when Governments censor necessary information in the name of not offending anyone, as seen here.

- Support INDUSTRY STANDARDS? So the internet “will” be regulated globally.

- And all of this misses a VERY IMPORTANT point: what happens when content is shared in Country A, but rules in Country B would render it illegal? Does the content get pulled down because it is offensive to some other nation in the world?

All in all, this is pretty chilling.

4. From Global(ist) News Article

“The platforms are failing their users. And they’re failing our citizens. They have to step up in a major way to counter disinformation, and if they don’t, we will hold them to account and there will be meaningful financial consequences,” he said Thursday.

.

“It’s up to the platforms and governments to take their responsibility seriously and ensure that people are protected online. You don’t have to put the blame on people like Mark Zuckerberg or dismiss the benefits of social platforms to know that we can’t rely exclusively on companies to protect the public interest,” Trudeau continued.

.

He announced that Canada would be launching a digital charter, touching on principles including universal access and transparency and serving as a guide to craft new digital policy.

.

Speaking about Canada’s upcoming federal election, he said the government was taking steps to eliminate fake news and that a new task force had been created in order to identify threats to the election and prevent foreign interference.

5. Remember? $595M Bribe

A New Non-Refundable Tax Credit for Subscriptions to Canadian Digital News Media

.

To support Canadian digital news media organizations in achieving a more financially sustainable business model, the Government intends to introduce a new temporary, non-refundable 15-per-cent tax credit for qualifying subscribers of eligible digital news media.

.

In total, the proposed access to tax incentives for charitable giving, refundable tax credit for labour costs and non-refundable tax credit for subscriptions will cost the federal government an estimated $595 million over the next five years. Additional details on these measures will be provided in Budget 2019.

Not only will the Trudeau Government be cracking down on what it views as “fake news”, it will be subsidizing “friendly” or cooperative media. This is nothing short of propaganda. This is a government propping up dying media outlets financially. Of course, what will be expected in return? favourable coverage?

6. Section 2: Fundamental Freedoms

To summarize so far, our government:

(1) Is a member of the UN, which wants to globally regulate the internet. This is referred to as “DIGITAL COOPERATION”. The same UN wants to globally ban criticism of Islam.

(2) Passes a “non-binding” motion, M-103, to ban Islamophobia.

(3) Passes Bill C-16, to ban criticism of their gender agenda, calling certain language to be hate speech.

(4) Signs the Global Migration Compact, which contains provisions (Objective 17(c)) to sensitise and regulate media.

(5) Announces plans to subsidize “certain” media, the 2018 economic update.

(6) Attends a convention, the Christchurch call, and signs the above resolution.

(7) Announces plans for a “digital charter”

Can Section 2 of the Charter — fundamental freedoms — protect us from this assault on free speech? Let’s hope so:

Fundamental freedoms

2. Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:

(a) freedom of conscience and religion;

(b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication;

(c) freedom of peaceful assembly; and

(d) freedom of association.

Most court cases have come down on the side of fundamental freedoms. If this digital charter comes to be, then certainly the 2 charters will collide.

7. Doing What UN Never Could?

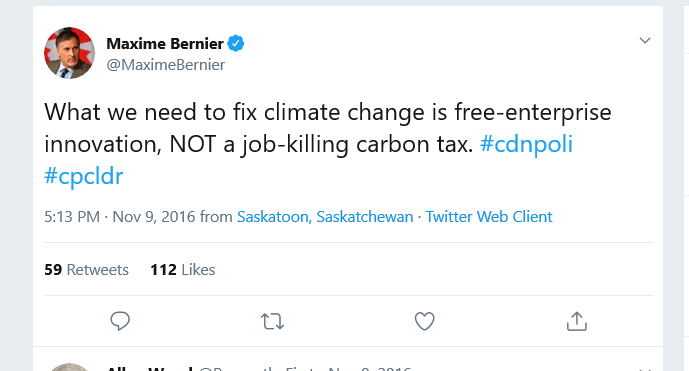

The UN has for a long time tried to regulate our freedoms for the “global collective” or some other such nonsense.

But now, will we do this to ourselves? Will Western nations engage in their own freedom-suicide pact in order to provide the illusion of security from violent terrorists and extremists?

Western Liberals embrace global rule and regulation. So do “Conservatives”, and fake populists, who are basically globalists in disguise. It will be interesting to see how many will actually stand up for freedom instead of caving to pressure.