(A brief, promotional video)

1. Important Links

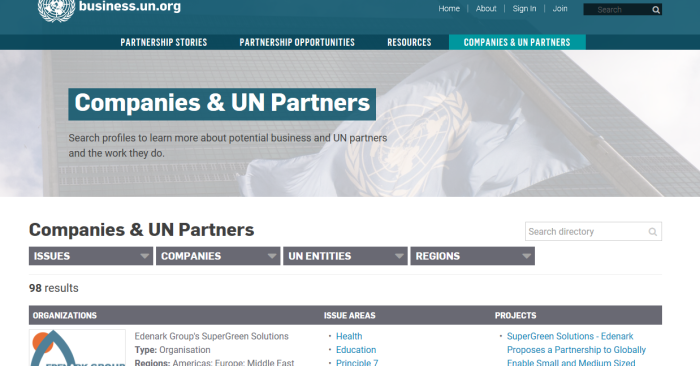

(1) https://business.un.org

(2) https://www.crossroads.org.hk/global-hand/

(3) https://business.un.org/en/browse/companies_entities

(4) https://business.un.org/documents/resources/un-business-partnership-handbook.pdf

2. What Do They Do?

The UN-Business Action Hub was developed as a joint effort of the United Nations Global Compact, Global Hand, a Hong-Kong based non-profit specializing in facilitating private sector and NGO connections, and 20 UN entities and aims to foster greater collaboration between the business and UN to advance solutions to global challenges and to support various humanitarian and disaster preparedness and response efforts.

On this platform business can learn more about UN entities, their mandates, specific needs, and offer programmatic support, in-kind and financial donations, while UN entities can learn more about the specific interests of companies, available resources and engagement opportunities desired by business.

Additionally, both UN and Business can post projects and use the platform to search for and interact with potential partners to scale the impact of their projects.

Join the hub and start interacting!

In a nutshell, this is the relationship:

(1) UN gets backers to support its globalist agenda, and

(2) Companies become more known and get free advertising

3. The Partnership Handbook

Foreword

Executive Summary

1. Purpose of the handbook

2. Things to consider before creating a new partnership

- Creating an enabling environment

- Defining desired outcomes

3. Building the appropriate partnership

- Building Block 1: Choose the partnership’s composition

- Block 2: Define the roles of each partner

- Building Block 3: Draft a roadmap for the partnership

- Building Block 4: Define the partnership’s scope

- Building Block 5: Design a governance structure for the partnership

- Building Block 6: Decide how to finance the partnership

- Building Block 7: Decide how to monitor and evaluate the partnership

4. Identifying established UN-business partnership models

- Partnership model 1: Global implementation partnerships

- Partnership model 2: Local implementation partnerships

- Partnership model 3: Corporate responsibility initiatives

- Partnership model 4: Advocacy campaigns

- Partnership model 5: Resource mobilization partnerships

- Partnership model 6: Innovation partnerships

Glossary of terms

This 64 page handbook reads like a typical partnership agreement or memorandum of understanding would, at least in some sense it does.

Of course, if you are going to partner with someone, you want information about the other party. You also want to discuss things like financing, goals, and division of labour. This is common sense, and anyone with any business sense would know this already.

The weird parts (at least for me), are several:

- Among “partners”, UN lists 42 of its own departments

- Everything is couched in social justice terms

- EXTREMELY wordy, but a lot of common sense

- Seems like a way to simply cash in on UN agendas

- A lot of “implied” consent of host populations

4. Financing A Partnership

UN entities often partially absorb costs of partnerships, for example, if salaries for practitioners, travel expenses or administrative costs are covered by their own funds, in the following described as UN institutional funds. Further required funds come from business partners or involved governmental institutions. Besides that, partnerships can conduct external fundraising activities, for example, by establishing social media platforms for donating cash, such as WFP’s WeFeedback Website, or in rarer cases, international finance facilities, which issue bonds against the security of government guarantees, such as achieved by the GAVI Alliance. Finally, foundations have increasingly become an external source for funds, above all the UN foundation.

If partnerships address local problems or strive for policy impact, related governments can be approached for additional funds. Governments might also provide funds if partnerships’ approaches correspond with their priorities, for example, fighting climate change. Drawing on funds from governmental institutions does, however, also include them as partners, which is in principle desirable, but can run the risk of politicizing partnerships or slowing them down due to government bureaucracies. External fundraising activities can provide access to potentially huge financial resources not successfully leveraged by the UN so far such as donations from private households. They also have a positive side effect by raising awareness for development problems. However, as the amount of funds raised externally cannot always be predicted, such campaigns are better suited for scaling-up existing programs rather than launching new ones.

UN entities and business partners provide the bulk of funds for UN-business partnerships and the ratio of provided UN to business funds has a strong effect on partnership governance. If partnerships draw most financial resources from UN institutional funds, UN entities can maximize negotiating power vis-àvis business partners and most likely control decision-making. However, without a stake in decision-making and invested resources, companies may have less incentive to contribute to partnership activities. Such partnerships also tend to be limited in scope as UN entities have restricted financial resources, often far below those of companies.

5. Final Thoughts

An interesting takeaway from this is the plain acknowledgement that whoever contributes more, has more leverage in the bargaining.

Also implied is the idea that local governments can be persuaded to shell out public tax money if they can be persuaded that it aligns with their priorities.

This business action hub seems to be a global “Chamber of Commerce”, where businesses can connect with UN agencies. Social justice meets capitalism. What could go wrong?

Discover more from Canuck Law

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.