(From actual academic writing: Frank W. Geels)

(More academia: Sustainable Consumption Institute, Manchester University)

(Clayton Christiansen and “Disruptive Innovation” video)

(From the Uppity Peasants site)

1. Go Check Out Uppity Peasants Site

This is a fairly new site, however, it has some interesting content on it. Well researched, it will give some alternative views on how we are really being controlled.

Go check out “Uppity Peasants“.

2. Important Links

CLICK HERE, for the Sustainable Consumption Institute & Manchester Institute of Innovation Research, The University of Manchester, Denmark Road Building, M13 9PL, Manchester, United Kingdom.

CLICK HERE, for Clayton Christiansen and “Disruptive Innovation”.

CLICK HERE, for SCI Collective Action & Social Movements.

CLICK HERE, for SCI Social Inequality.

CLICK HERE, for Multi-Level Perspective on Sustainability.

CLICK HERE, for a Wiki explanation of disruptive innovation.

CLICK HERE, for removing the innovator’s dilemma.

CLICK HERE, for the Climate Change Scam Part I.

CLICK HERE, for Part II, the Paris Accord.

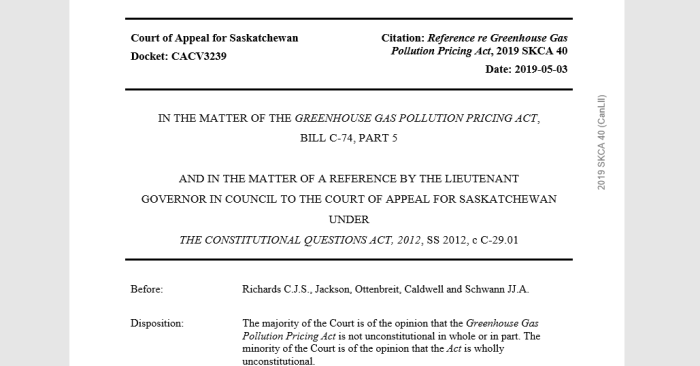

CLICK HERE, for Part III, Saskatchewan Appeals Court Reference.

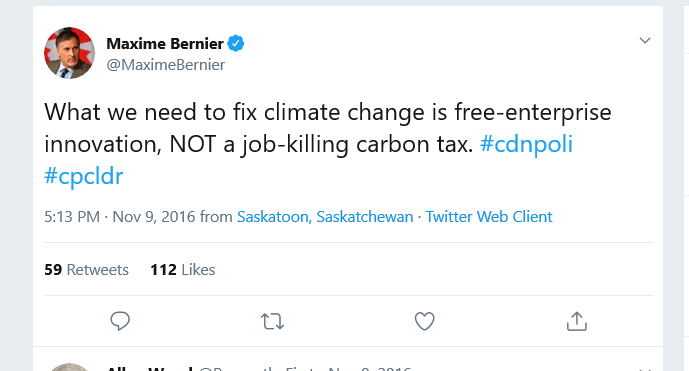

CLICK HERE, for Part IV, Controlled Opposition to Carbon Tax.

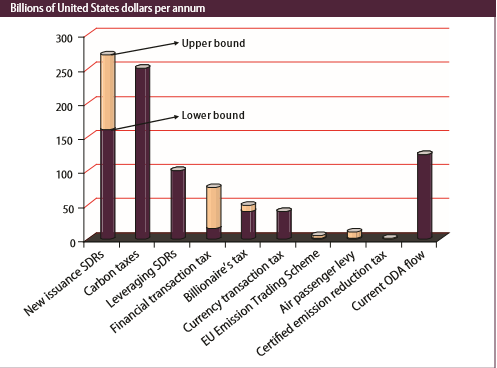

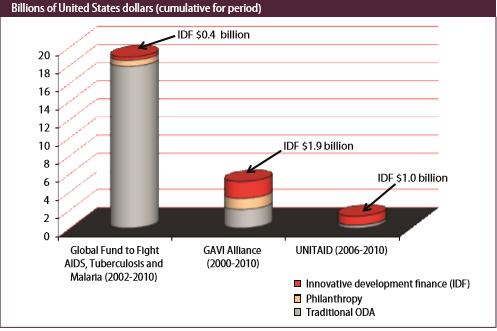

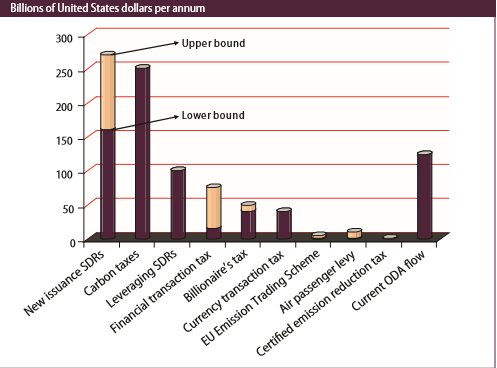

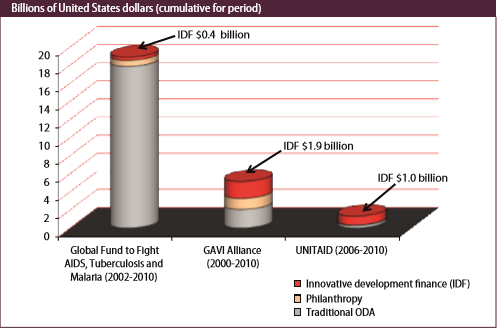

CLICK HERE, for Part V, UN New Development Funding.

3. Quotes From The Geels Article

Disruption and low-carbon system transformation: Progress and new challenges in socio-technical transitions research and the Multi-Level Perspective

This will be elaborated on, but is about subverted the status quo, or “disruption”. Worth pointing out, that although these types of articles are published and marketed as “science”, they are anything but.

As this title would suggest, the article is extremely political. The concern is not about science itself, but how to “sell” the science. And the agenda here is searching for political methods of implementing the transition to a Carbon free

ABSTRACT

This paper firstly assesses the usefulness of Christensen’s disruptive innovation framework for low-carbon system change, identifying three conceptual limitations with regard to the unit of analysis (products rather than systems), limited multi-dimensionality, and a simplistic (‘point source’) conception of change. Secondly, it shows that the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) offers a more comprehensive framework on all three dimensions. Thirdly, it reviews progress in socio-technical transition research and the MLP on these three dimensions and identifies new challenges, including ‘whole system’ reconfiguration, multi-dimensional struggles, bi-directional niche-regime interactions, and an alignment conception of change. To address these challenges, transition research should further deepen and broaden its engagement with the social scienceseconomy.

The usefulness of Christiansen’s disruptive innovation framework? While used in a business sense, it appears to be a way for entrepreneurs to get into a market or business. However, in this context it is used as disrupting an environmental policy.

It is mildly (or downright) creepy that the author, Frank Geels, openly suggests that research should broaden its engagement with social sciences. In plain English, this means merging, where scientific research is viewed through a “social” lens.

Christiansen’s “Disruptive Innovation Framework” is explained in the above video. Also see “disruption in financial services“.

Christensen [4] made important contributions to the long-standing debate in innovation management about new entrants, incumbents and industry structures. He argued that disruptive innovations enable new entrants to ‘attack from below’ and overthrow incumbent firms. Christensen thus has a particular understanding of disruption, focused mainly on the competitive effects of innovations on existing firms and industry structures. His framework was not developed to address systemic effects or broader transformations, so my comments below are not about the intrinsic merits of the framework, but about their usefulness for low-carbon transitions.

Christensen’s disruptive innovation framework offers several useful insights for low-carbon transitions (although similar ideas can also be found elsewhere). First, it suggests that incumbent firms tend to focus their innovation efforts on sustaining technologies (which improve performance along established criteria), while new entrants tend to develop disruptive technologies (which offer different value propositions). Second, it proposes that disruptive technologies emerge in small peripheral niches, where early adopters are attracted by the technology’s new functionalities. Third, incumbent firms may initially overlook or under-estimate disruptive technologies (because of established beliefs) or are not interested in them, because the limited return on-investments associated with small markets do not fit with existing business models. Fourth, price/performance improvements may enable disruptive technologies to enter larger markets, out-compete existing technologies and overthrow incumbent firms

Worth pointing out right away, Geels has no interest in the “intrinsic merits” of the disruptive innovation framework that Christiansen talks about. Rather, he focuses on applying that technique to reducing/eliminating Carbon emissions from society.

Christiansen’s idea could be applied fairly practically to business, where new players want to establish themselves. However, Geels “weaponizes” this idea and wants to apply it with the climate-change agenda.

Geels also makes it obvious that overthrowing incumbents is a priority. Again, Christiansen’s writings were meant with the business approach, and trying to start your own, but Geels “repurposes” it.

While Christensen’s framework focuses on technical and business dimensions, the MLP also accommodates consumption, cultural, and socio-political dimensions. Although co-evolution has always been a core concept in the MLP, this is even more important for low-carbon transitions, which are goal-oriented or ‘purposive’ in the sense of addressing the problem of climate change. This makes them different from historical transitions which were largely ‘emergent’, with entrepreneurs exploiting the commercial opportunities offered by new technology

[27]. Because climate protection is a public good, private actors (e.g. firms, consumers) have limited incentives to address it owing to free rider problems and prisoner’s dilemmas. This means that public policy must play a central role in supporting the emergence and deployment of low-carbon innovations and changing the economic frame conditions (via taxes, subsidies, regulations, standards) that incentivize firms, consumers and other actors. However, substantial policy changes involve political struggles and public debate because: “[w]hatever can be done through the State will depend upon generating widespread political support from citizens within the context of democratic rights and freedoms” ([28]: 91).

Again, Geels hijacking a legitimate business concept, but using it for his enviro agenda.

How to implement this? Taxes, subsidies, regulations, standards for businesses and consumers. Use these to regulate and influence behaviour.

Geels rightly says that widespread political support will be needed. But he frames the climate change scam as a way to protect rights and freedoms. Nice bait-and-switch.

Conceptually, this means that we should analyse socio-technical transitions as multi-dimensional struggles between niche-innovations and existing regimes. These struggles include: economic competition between old and new technologies; business struggles between new entrants and incumbents; political struggles over adjustments in regulations, standards, subsidies and taxes; discursive struggles over problem framings and social acceptance; and struggles between new user practices and mainstream ones.

Despite Geels’ article being published in the Journal, “ENERGY RESEARCH AND SOCIAL SCIENCE”, this anything but scientific. If anything, it seems analogous to the “lawfare” that Islamic groups perpetuate on democratic societies.

While Geels promotes economic competition, this is anything but a fair competition. He also calls for:

- Political struggles over regulations

- New standards

- Subsidies

- Taxes

- Discursive struggles over problem framings & social acceptance

- Struggles between new and mainstream user practices

There is nothing scientific here. This is a call for using “political” manoeuvering for achieving social goals.

The importance of public engagement, social acceptance and political feasibility is often overlooked in technocratic government strategies and model-based scenarios, which focus on techno-economic dimensions to identify least-cost pathways [32]. In the UK, which is characterized by closed policy networks and top-down policy style, this neglect has led to many problems, which are undermining the low carbon transition.

• Onshore wind experienced local protests and permit problems, leading to negative public discourses and a political backlash, culminating in a post-2020 moratorium.

• Shale gas experienced public controversies after it was pushed through without sufficient consultation.

• Energy-saving measures in homes were scrapped in 2015, after the Green Deal flagship policy(introduced in2013) spectacularly failed, because it was overly complicated and poorly designed, leading to limited uptake.

• The 2006 zero-carbon homes target, which stipulated that all new homes should be carbon-neutral by 2016, was scrapped in 2015, because of resistance by major housebuilders and limited consumer interest.

• The smart meter roll-out is experiencing delays, because of controversies over standards, privacy concerns, and distribution of benefits (between energy companies and consumers).

While these points are in fact true, Geels suggests that problems could have been avoided if there was sufficient public consultation. This is wishful thinking.

These points raise many legitimate concerns with the eco-agenda. Yet Geels shrugs them off as the result of not engaging the public enough.

Christensen and other innovation management scholars typically adopt a ‘point source’ approach to disruption, in which innovators pioneer new technologies, conquer the world, and cause social change. Existing contexts are typically seen as ‘barriers’ to be overcome. This ‘bottom-up’ emphasis also permeates the Strategic Niche Management and Technological Innovation System literatures. While this kind of change pattern does sometimes occur, the MLP was specifically developed to also accommodate broader patterns, in which niche-innovations diffuse because they align with ongoing processes at landscape- or regime-levels [9].

The MLP thus draws on history and sociology of technology, where processual, contextual explanations are common. Mokyr [58], for instance, emphasizes that “The new invention has to be born into a socially sympathetic environment” (p. 292) and that “Macro-inventions are seeds sown by individual inventors in a social soil. (.) But the environment into which these seeds are sown is, of course, the main determinant of whether they will sprout” (p. 299). So, if radical innovations face mis-matches with economic, socio-cultural or political contexts, they may remain stuck in peripheral niches, hidden ‘below the surface’.

Since low-carbon transitions are problem-oriented, transition scholars should not only analyse innovation dynamics, but also ‘issue dynamics’ because increasing socio-political concerns about climate change can lead to changes in regime-level institutions and selection environments. Societal problems or ‘issues’ have their own dynamics in terms of problem definition and socio-political mobilization as conceptualized, for instance, in the issue lifecycle literature [59,50]. Low carbon transitions require stronger ‘solution’ and problem dynamics, and their successful alignment, which is not an easy process, as the examples below show.

These passages go into marketing strategies, and ways to “frame an argument”. Notice not once does Geels suggest doing more research, or checking the reliability of existing data. Instead, this is a push for emotional manipulation and shameless advertising.

Invention has to be born into a socially sympathetic environment. Science be damned.

There are also positive developments, however, that provide windows of opportunity. Coal is losing legitimacy in parts of the world, because it is increasingly framed as dirty, unhealthy and old-fashioned, and because oil and gas companies are distancing themselves from coal, leading to cracks in the previously ‘closed front’ of fossil fuel industries. The UK has committed to phasing out coal-fired power plants by 2025 and several other countries (Netherlands, France, Canada, Finland, Austria) also move in this direction, providing space for low-carbon alternatives, including renewables.

I would actually agree that coal being phased out would benefit society. However, Geels makes it a “marketing” issue rather than a scientific one. Coal is “increasingly framed” as dirty. Notice that the actual science, such as from this site, are very rarely described.

Following chemical reactions takes place in the combustion of coal with the release of heat:

C + O2 = CO2 + 8084 Kcal/ Kg of carbon (33940 KJ/Kg)

S + O2 = SO2 + 2224 Kcal/Kg of sulfur (9141 KJ/Kg)

2 H2 + O2 = 2 H2O + 28922 Kcal/Kg of hydrogen (142670 KJ/Kg)

2C + O2 = 2CO + 2430 Kcal/Kg of carbon (10120 KJ/Kg)

4. Geels’ Conclusions

The paper has also identified several research challenges, where the transitions community could fruitfully do more work. First, we should broaden our analytical attention from singular niche-innovations (which permeate the literature) to ‘whole system’ change. This may involve changes in conceptual imagery (from ‘point source’ disruption to gradual system reconfiguration) and broader research designs, which analyze multiple niche-innovations and their relations to ongoing dynamics in existing systems and regimes. That, in turn, may require more attention for change mechanisms like add-on, hybridisation, modular component substitution, knock-on effects, innovation cascades, multi regime interaction.

Second, we should better understand regime developments. Existing regimes can provide formidable barriers for low-carbon transitions. Incumbent actors can resist, delay or derail low-carbon transitions, but they can also accelerate them if they reorient their strategies and resources towards niche-innovations. The analysis of niche-to-regime dynamics (as in the niche empowerment literature) should thus be complemented with regime-to-niche dynamics, including incumbent resistance or reorientation. Additionally, we need more nuanced conceptualizations and assessments of degrees of lock-in, tensions, cracks, and destabilisation.

Third, we need greater acknowledgement that socio-technical systems are a special unit of analysis, which spans the social sciences and can be studied through different lenses and at different levels. The recent trend towards deepening our understanding of particular dimensions and societal groups is tremendously fruitful, because disciplinary theories offer more specific causal mechanisms. But, as a community, we should complement this with broad analyses of co-evolution, alignment, multi-dimensionality and ‘whole systems’.

This all sounds elegant, but read between the lines. It is about influencing public perception. Whenever academics, lawyers or politicians seem to make things confusing we need to ask: are they trying to obscure their goals?

5. More About Frank W. Geels

Selected publications of Geels

If you would like a broader cross section of Geels’ work, perhaps these publications will be of interest.

- Geels, F.W., Berkhout, F. and Van Vuuren, D., 2016, Bridging analytical approaches for low-carbon transitions, Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 576-583

- Geels, F.W., Kern, F., Fuchs, G., Hinderer, N., Kungl, G., Mylan, J., Neukirch, M., Wassermann, S., 2016, The enactment of socio-technical transition pathways: A reformulated typology and a comparative multi-level analysis of the German and UK low-carbon electricity transitions (19902014), Research Policy, 45(4), 896-913

- Turnheim, B., Berkhout, F., Geels, F.W., Hof, A., McMeekin, A., Nykvist, B., Van Vuuren, D., 2015, Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges, Global Environmental Change, 35, 239–253

- Penna, C.C.R. and Geels, F.W., 2015, ‘Climate change and the slow reorientation of the American car industry (1979-2011): An application and extension of the Dialectic Issue LifeCycle (DILC) model’, Research Policy, 44(5), 1029-1048

- Geels, F.W., 2014, ‘Regime resistance against low-carbon energy transitions: Introducing politics and power in the multi-level perspective’, Theory, Culture & Society, 31(5), 21-40

- Geels, F.W., 2013, ‘The impact of the financial-economic crisis on sustainability transitions: Financial investment, governance and public discourse’, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 6, 67-95

- Geels, F.W., 2012, ‘A socio-technical analysis of low-carbon transitions: Introducing the multi-level perspective into transport studies’, Journal of Transport Geography, 24, 471-482

- Geels, F.W., Kemp, R., Dudley, G. and Lyons, G. (eds.), 2012, Automobility in Transition? A Socio Technical Analysis of Sustainable Transport, New York: Routledge

- Verbong, G.P.J. and Geels, F.W., 2010, ‘Exploring sustainability transitions in the electricity sector with socio-technical pathways’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(8), 12141221 Verbong, G.P.J. and Geels, F.W., 2007, ‘The ongoing energy transition: Lessons from a sociotechnical, multi-level analysis of the Dutch electricity system (1960-2004)’, Energy Policy, 35(2), 1025-1037

- Geels, F.W., 2002, ‘Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study’, Research Policy, 31(8/9), 1257-1274

Frank Geels publicly available CV

Education

• Ph.D., Science, Technology and Innovation Studies, Twente University of Technology (Jan. 1998- July 2002), Netherlands. Supervisors: Arie Rip and Johan Schot. Title PhD thesis: Understanding the Dynamics of Technological Transitions: A co-evolutionary and socio-technical analysis.

• Masters degree in Philosophy of Science, Technology and Society, Twente University of Technology (1991-1996)

• Bachelor degree in Chemical Engineering, Twente University of Technology (1989-1991)

For what it’s worth, his formal education is pretty impressive. Where I lose respect is when he deviates from scientific argument in favour of political discourse. What could be very interesting work is corrupted be having an agenda.

His undergraduate degree is chemical engineering, which again, is very respectable. However, his Masters and PhD show a deviation from science and research.

While there are many other such authors, Frank W. Geels is a good case of what happens when political agendas and manoeuvering creep into science.

A morbidly fascinating topic. Check out some of his other publications.