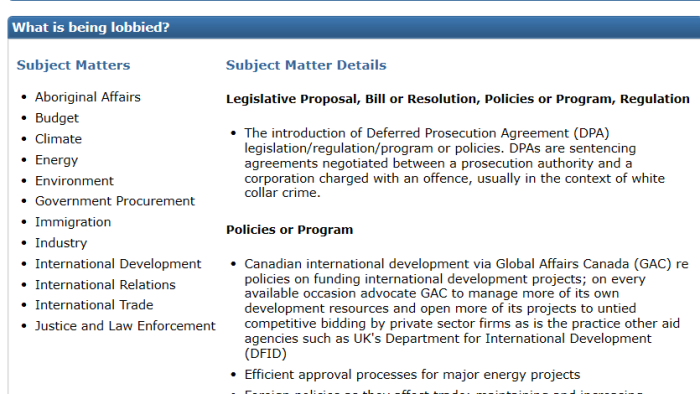

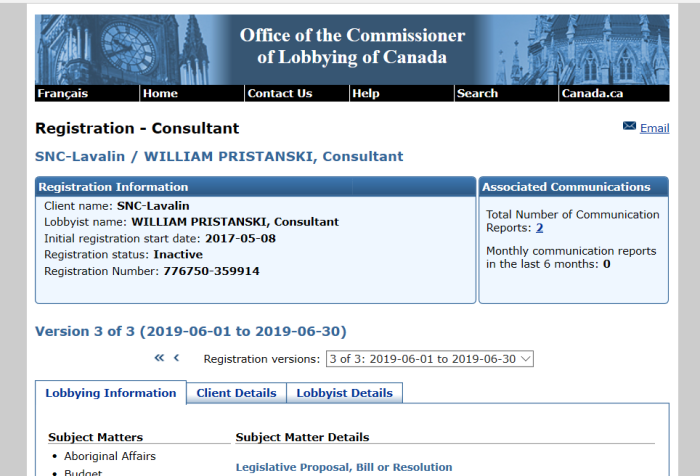

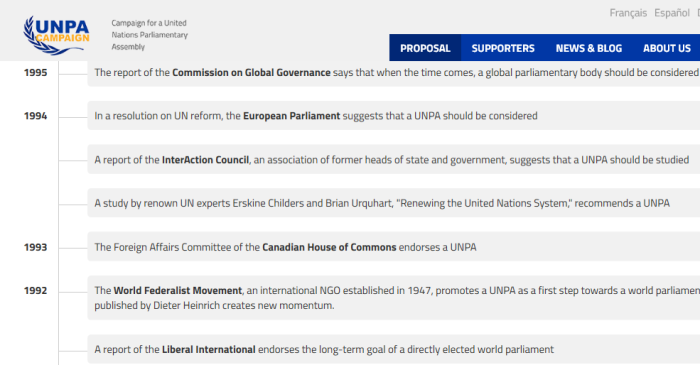

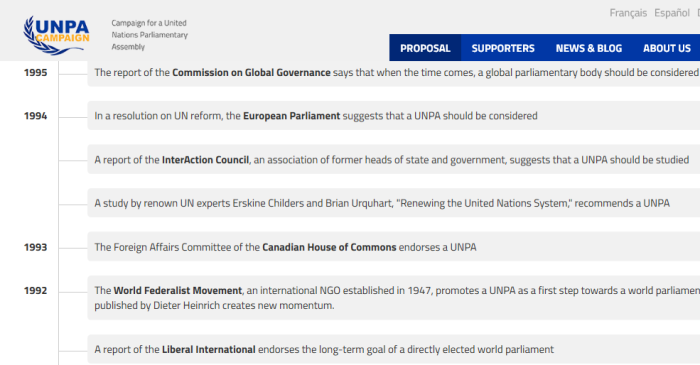

(Canada’s House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee approved the idea of a UN Parliament in 1993, and again in 2007)

1. Important Links

(1) https://canucklaw.ca/un-parliamentary-assembly-proposed-a-k-a-global-government/

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Parliamentary_Assembly#cite_note-24

(3) http://archive.is/mslRy

(4) Wayback Machine, for archive of 1993, 8th Report, Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade, House of Commons, Parliament of Canada, Spring 1993, chaired by Hon. Jon Bosley.

(5) https://web.archive.org/web/20071229011523/http://www.worldfederalistscanada.org/0896unpa.html

(6) http://archive.is/e9IMH

(7) https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/committee/391/faae/reports/rp3066139/391_FAAE_Rpt08_PDF/391_FAAE_Rpt08-e.pdf

(8) CLICK HERE, for “conservative” Senator Douglas Roche.

(9) https://en.unpacampaign.org/proposal/

(10) http://archive.is/GMgwO

(11) https://en.unpacampaign.org/supporters/survey/

(12) http://archive.is/KpIqW

(13) https://en.unpacampaign.org/supporters/overview/?mapcountry=CA&mapgroup=mem

(14) http://archive.is/P7ZS9

(15) https://en.unpacampaign.org/meetings/november2007/

(16) http://archive.is/NKaj8

(17) http://archive.is/kRdVJ

(18) https://en.unpacampaign.org/meetings/november2008/

(19) http://archive.is/z1jUo

(20) http://archive.is/tNX9Z

(21) https://en.unpacampaign.org/239/establishment-of-a-global-parliament-discussed-at-international-meeting-in-new-york/

(22) http://archive.is/5lMyX

(23) http://archive.is/dXbo6

(24) https://en.unpacampaign.org/265/declaration-calls-for-intergovernmental-conference-on-un-parliament/

(25) http://archive.is/dXbo6

(26) https://en.unpacampaign.org/311/post-2015-agenda-should-include-elected-un-assembly-to-strengthen-democratic-participation/

(27) http://archive.is/xloAX

(28) http://archive.is/I4Mtb

2. Context For This Article

While the story of the United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) is still in the news, it is still a theory, at least for now.

However, Canada’s globalist politicians have been at it since well before 2007. In fact, Brian Mulroney’s Government originally approved the idea in 1993.

Why should Canadians care? Well, if you think getting fair and adequate representation from Ottawa is difficult, try getting it from a global government.

3. Timeline For UN Parliament

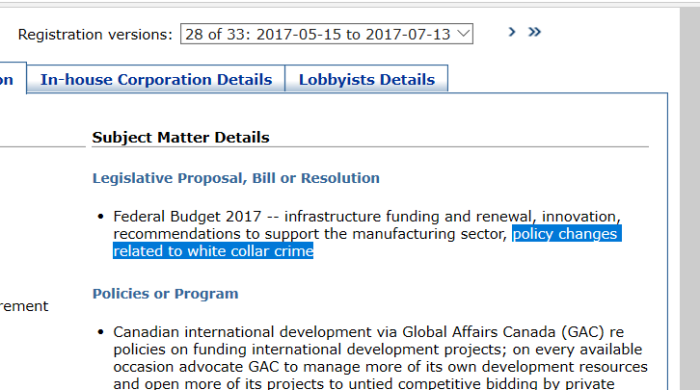

- Spring 1993 – CDA HoC Foreign Affairs Comm endorses UNPA

- July 1993 – Brian Mulroney replaced by Campbell as PM

- October 1993 – Jean Chretien elected as PM

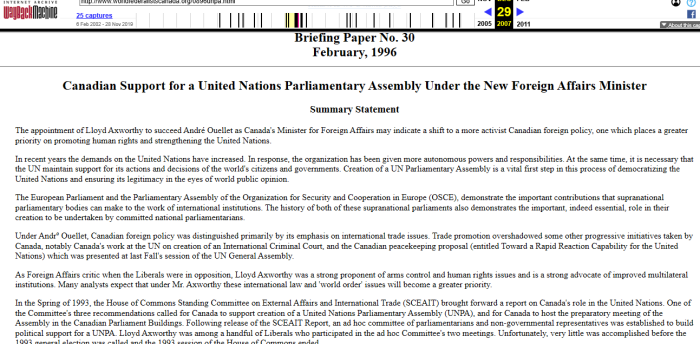

- 1996 – Support in Chretien’s Gov’t for UNPA

- 2002 – Sen. Douglas Roche endorses UNPA

- January 2006 – Harper replaces Martin as PM

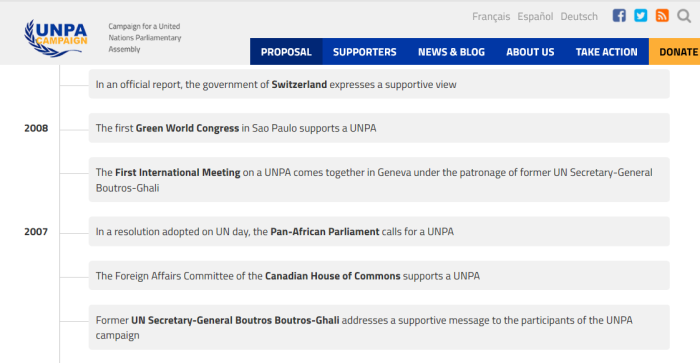

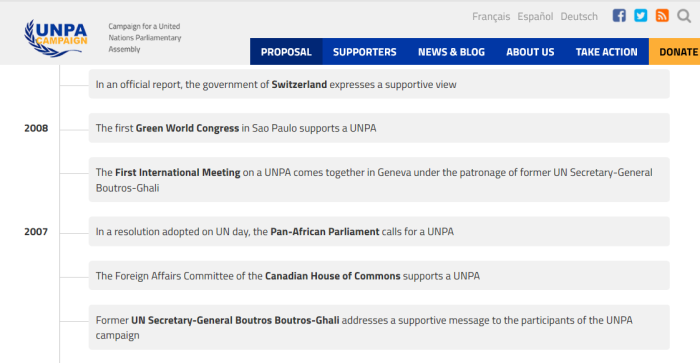

- July 2007 – CDA HoC Foreign Affairs Comm endorses UNPA

- August 2007 – Bernier replaces MacKay as FA Minister

- November 2007 – First UNPA Int’l Meeting, Switzerland

- November 2008 – Second UNPA Int’l Meeting, Belgium

- October 2009 – Third UNPA International Meeting, USA

- July 2010 – Trudeau endorses UNPA as an MP

- October 2010 – Fourth UNPA Int’l Meeting, Argentina

- October 2013 – Fifth UNPA Int’l Meeting, Belgium

4. Quotes From 1993 Standing Comm Report

The decline in Canadian support for things international – and the decline is palpable – is explained more by loss of self-confidence among Canadians than by lack of caring. There is no more important task before us than to recover some of that confidence and no more important means of doing so than through the empowerment of the United Nations. People must see that the centre can hold and that they have a role to play in making it so.

By way of building the public and political constituency for the United Nations, the Committee recommends that Canada support the development of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (21) and that we offer to host the preparatory meeting of the Assembly in the Parliament Buildings as the centrepiece in our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations in 1995. We would further recommend that the Government work closely with the national organizing committee for the 50th anniversary and encourage the active participation of non-governmental organizations in the planning and holding of the Assembly.

Conclusion

.

In closing this long letter the Committee wishes to commend the Government for being one of the few that has contributed energetically to keeping An Agenda for Peace alive. But alive is not good enough. Much more needs to be done. The proposals of the Secretary General should be the beginning of a vital international process of reform and renewal of the United Nations system. Canada should work hard to help make it so. The Committee intends to keep the empowerment of the UN high on its agenda and to hold additional hearings in the new session of Parliament. We would ask that the Minister respond in writing to this letter by early May.

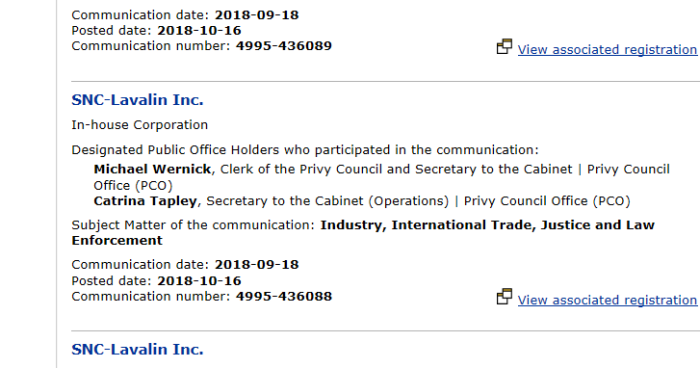

This is what it sounds like. The Mulroney Government, which calls itself “conservative”, has the Foreign Affairs Committee approve in principle participation in a United Nations Parliament.

Note: Mulroney had a huge majority at that time, so there was no real need to get opposition approval on this. So no one can say he was pressured into doing it.

5. Approval Of UNPA In 1996

In recent years the demands on the United Nations have increased. In response, the organization has been given more autonomous powers and responsibilities. At the same time, it is necessary that the UN maintain support for its actions and decisions of the world’s citizens and governments. Creation of a UN Parliamentary Assembly is a vital first step in this process of democratizing the United Nations and ensuring its legitimacy in the eyes of world public opinion.

The European Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), demonstrate the important contributions that supranational parliamentary bodies can make to the work of international institutions. The history of both of these supranational parliaments also demonstrates the important, indeed essential, role in their creation to be undertaken by committed national parliamentarians.

Under Andrº Ouellet, Canadian foreign policy was distinguished primarily by its emphasis on international trade issues. Trade promotion overshadowed some other progressive initiatives taken by Canada, notably Canada’s work at the UN on creation of an International Criminal Court, and the Canadian peacekeeping proposal (entitled Toward a Rapid Reaction Capability for the United Nations) which was presented at last Fall’s session of the UN General Assembly.

As Foreign Affairs critic when the Liberals were in opposition, Lloyd Axworthy was a strong proponent of arms control and human rights issues and is a strong advocate of improved multilateral institutions. Many analysts expect that under Mr. Axworthy these international law and ‘world order’ issues will become a greater priority.

In the Spring of 1993, the House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade (SCEAIT) brought forward a report on Canada’s role in the United Nations. One of the Committee’s three recommendations called for Canada to support creation of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA), and for Canada to host the preparatory meeting of the Assembly in the Canadian Parliament Buildings. Following release of the SCEAIT Report, an ad hoc committee of parliamentarians and non-governmental representatives was established to build political support for a UNPA. Lloyd Axworthy was among a handful of Liberals who participated in the ad hoc Committee’s two meetings. Unfortunately, very little was accomplished before the 1993 general election was called and the 1993 session of the House of Commons ended.

The New Liberal Chretien Government shares the globalist appetite and ideas that the previous Mulroney Government did. More support for creating of the actual world government.

6. Senator Douglas Roche & UNPA, 2002

The arguments below contain these assumptions in their essence. However, it is understood (perhaps reluctantly) that world federalism and the end of the state system is not in the mainstream political agenda for a contemporary UN. The objectives of UN reform and addressing issues of international governance are reasonable and feasible in contemporary politics. Implications for a Kantian vision of world federalism can be bruited, but at this point not much more.1 A UNPA would not be a world parliament, although some supporters and detractors of a UNPA think of it as a step towards a form of world government or global federalism.

World government is not a necessary criterion in discussing a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly. World government is not the case here. What is at issue is governance, by which is commonly understood to be the regulation of an increasingly complex and interconnected world comprising States, societies, corporations, individuals and epistemic communities.

The question of a UNPA, then, becomes one relating to a UNPA within the UN system and a UNPA within both the growing interconnectedness of trans-national politics and existing networks of global governance. Governance, transparency, democracy, diplomacy and international norms of behaviour – how states behave when their affairs are so intertwined – these are the issues in the background when discussing the formation of a UNPA.4 Specifically discussed below are those aspects of these phenomena that today seem to drive the argument for a UNPA.

Some nice double speak here. Senator Roche is trying to argue that a United Nations Parliament would not actually amount to a world government. Okay.

7. Quotes From 2007 Standing Comm Report

CHAPTER 8 CANADA’S ROLE IN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND MULTILATERAL APPROACHES TO DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT

[W]e need democracy as a basis of a safer world, we need democracy as the basis for a just system of international relations …

Her Excellency Nino Burjandze, Speaker of the Parliament of Georgia

The Committee has already made reference in previous chapters to Canada’s welcomed multilateralist approach to democratic development and to its valued contribution to multilateral bodies. We believe that should be continued, and enhanced where most effective, as part of the evaluation of all Canadian support for international democratic development that we have recommended.

The Committee observes as well that international organizations are increasingly expanding their work into all areas of democratic development and governance. For example, in our meeting at the Commonwealth Secretariat, its Secretary General told the Committee that the Secretariat is trying to work both at the cultural level and with parliaments and political parties on understanding the role of the opposition and on introducing accountability measures. Mr. Christopher Child, Advisor and Head of the Democracy Section, commented that “we’d like to do much more party training.” Strengthening party systems has also become an important area of work for the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Systems (IDEA). The role of political parties in democracy-building was the subject of the Council of Europe Forum for the Future of Democracy which took place in Moscow in October 2006 with the involvement of the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly to which Canada sends observers.

The World Bank, to which Canada is an important contributor through the Department of Finance, is not allowed by its Charter to take into account the nature of the political regime, hence its role in “political development is obviously constrained,” as Sanjay Pradhan, Sector Director in the Public Sector Governance Unit told the Committee in Washington, D.C. However, within a broader conception of good governance that is linked to democratic development: “We are doing a lot in terms of accountability of the state to its citizens.” So the Bank works on things that might be considered “building blocks” of democracy. Mr. Pradhan distributed a paper “How Ongoing Operations of the World Bank Currently Strengthen Participation and Accountability,” which lists six major program areas for Bank interventions. One of these includes “parliamentary capacity development.”

Mr. Steen Lau Jorgensen, Director of the Bank’s Sustainable Development Network, elaborated that the Bank has programs directly involving local communities in development decisions, thereby increasing the effectiveness of projects. In the Bank’s experience, more open countries do much better in achieving their development goals. The Bank therefore has an interest in building the capacity of civil society and it now even gets close to election-related processes, as in Ivory Coast where it is helping with the compiling of a national registration list. In this case, the Bank is working with the EU and the UN and through the country’s prime minister’s office. Registration is not just about elections but about establishing citizen’s eligibility for social services.

As Mr. Jorgensen put it, there has been a “fundamental change in mindset” towards seeing poor people as citizens having rights and responsibilities. The Bank’s consequent shift away from major infrastructure projects since the late 1980s has been approved by its Board. The Bank sees this as linked to development effectiveness, which incorporates a good governance and anti-corruption agenda. For example, in the public procurement process, the Bank has established oversight through a “Procurement Watch” mechanism, and it now has a “zero tolerance” policy on corruption in World Bank-supported projects. Mention was also made of a “Global Integrity Alliance” as part of an anti-corruption strategy involving leaders in the recipient countries.

The role of a major international financial institution like the World Bank is noteworthy in another sense, since many believe that these powerful international organizations are not themselves sufficiently democratically accountable to the publics in the countries which make up their memberships. Several of the Committee’s witnesses addressed the issue of the need to advance democratization processes from the local and national levels of governance, to the dimension of global governance. For example, John Foster of the North-South Institute referred to the Finnish-supported “Helsinki Process” which produced a 2005 Report, Governing Globalization-Globalizing Governance, that made recommendations for democratizing oversight of the global economy and strengthening the role of parliamentarians and civil society in that regard. He also made reference to the work of the Forum International de Montreal — which gets most of its funding from non-Canadian sources — and to the Spanish-based “World Forum of Civil Society Networks and its Campaign for an In-Depth Reform of the System of International Institutions…”

The presentation to the Committee by the World Federalist Movement — Canada also devoted a lot of attention to advancing democratization at the level of international institutions, in particular in the context of United Nations reforms. Indeed it noted that this Committee in 1993 had supported the concept of a parliamentary assembly at the UN, and it went on to state:

In April 2007, the Committee for a democratic UN (an NGO organizing network working with parliamentarians) will present publicly the “International Appeal for the Establishment of a United National Parliamentary Assembly, at press conferences around the world. Following the Appeal launch in April, an international parliamentary conference is planned for October 2007 in Geneva.

The World Federalist representatives urged the Committee to give favourable consideration to this international appeal. We note as well that the European Parliament has supported the establishment of UN Parliamentary Assembly as part of overall UN reform, most recently in a resolution of June 9, 2005.

In terms of working through international organizations, the biggest of all is of course the UN system. Most of the UN funding related to democratic development and governance goes through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Indeed, when the Committee met with the UNDP’s Pippa Norris, Director of the Democratic Governance Group, Bureau of Development Policy, and other senior staff (many of them Canadians) at the UN in New York, it was noted that this group is the largest within the UNDP.

Ms. Norris shared with the Committee the group’s Strategic Plan, 2008-2011, and explained that its mandate in the area of democratic governance comes from various UN sources including the Millennium Declaration and a General Assembly resolution in 2000, the 2002 statement Democratic Governance Practice in UNDP, and a recent high-level panel report Delivering As One. Documents provided to the Committee included the UNDP’s Global Programme on Parliamentary Strengthening, on Support for Arab Parliaments, on Strengthening the Role of Parliaments in Reconstruction and the Prevention of Conflicts, and the annual report of its Democratic Governance Thematic Trust Fund. There was also a briefing note on CIDA-UNDP collaboration in Afghanistan. On gender issues, the Committee was told that an international knowledge network on women and politics was to be launched in February 2007, centred on an on-line tool to help education in this area. In addition, the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) does a lot of work on civic education for women. On electoral assistance, it was noted that collaboration between Elections Canada and UNDP goes back as far as Cambodia in 1993. However, another Canadian staff member Elissar Sarrouh (Policy Advisor, Public Administration Reform) — who formerly worked at the Parliamentary Centre — added that Elections Canada is always short of resources. So when countries express interest in having Canadian expertise, sometimes the resources are not there.

On the UN’s work on election processes, the Committee also met with Craig Jenness (again, a Canadian), Director of the Electoral Assistance Division within the Department for Political Affairs, who explained that this takes the form both of direct electoral support, and work on electoral best practices. Rather than election observation, the UN focuses either on providing assistance to electoral offices in host countries, or on assisting with electoral operations as part of peacekeeping missions in places like the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Haiti. The budget is relatively small, with a dozen people at headquarters, although a large roster of people — including many Canadians — work around the world. Also, there is a small trust fund to allow the quick deployment of people when necessary to places like Nepal. Some 102 UN member states — and four non-member states have requested electoral assistance since 1992, and over 30 countries are now receiving or have requested such assistance — most of them in Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

One important reason UN help is requested is that this helps legitimate the result and get it accepted — for example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The UN does not work with countries unless asked by the host government or there is a Security Council mandate. The UN tries to not run elections themselves, but to assist the host government in setting up the necessary structures to do so. In post-conflict situations, a problem that often comes up is that everyone wants to win an election, but it is often difficult to convince the losers that there is a real role for oppositions. According to Mr. Jenness, “parliamentarians can help” with that since they can talk to colleagues in other countries on a peer-to-peer basis.

Before turning to UN’s innovation of a “Democracy Fund” in 2005, and Canada’s potential role in that, it is important to recognize that notwithstanding all of this work, many questions still surround the UN’s involvement in democratic development, as well as that of international organizations such as the Community of Democracies or alternatives, which can be more explicit than the UN about their pro-democracy aims since their memberships are limited to at least nominally democratic states.

In observing that “the UN has often been in a situation where it has been an advocate of democracy”, Jane Boulden, Canada Research Chair in International Relations and Security Studies at the Royal Military College of Canada, told the Committee:

There are a number of member states that are not happy about the fact that the UN should play a role in advocating democracy, even when it comes to post-conflict situations where parties have agreed to democracy as part of the peace agreement.

This relates partly to the ongoing questions about sovereignty. With the responsibility to protect, for example, there’s been an increasing acceptance that sovereignty is not sacrosanct, and for those who are resistant to these ideas, the idea that democratization or democracy is an important universal value is seen as yet another hook that western states can use as a criterion for intervention in states.

If democracy is to be put forward as a universal value, we need to be able to make that case more effectively than we are now. That’s a factor the United Nations is grappling with, but I think it goes across the board for states as well. On this point, the questions of perceptions relate as well to the image or the perception in a number of states that the UN engages in a number of double standards. Why do we, through the United Nations, react to some conflicts and by extension then deal with some post-conflict scenarios with resources and commitment, and not others? When we feed that into the broader question about whether democracy is a western value or not, you can see how the whole package becomes an issue.

Scepticism about UN multilateralism combined with the need to engage the United States multilaterally has led to various alternatives being suggested. For example, two prominent U.S. scholars have recently made a detailed proposal for the establishment of a 60-member “Concert of Democracies.”

Yet to get around the fact that the UN includes many non-democracies, there has already been the creation of the Community of Democracies in 2000, with Canada as a founding member, and which met for the first time at the UN in 2004 as a UN “Democracy Caucus”. The Committee was told during our New York meetings in February 2007 that the 100-member “Caucus” is currently chaired by Mali, which is also an active member of the Group of New and Restored Democracies. His Excellency, Cheick Sidi Diarra, Ambassador and Permament Representative to the UN of Mali, was among a group of UN ambassadors and permanent representatives with whom the Committee met. We have already referred in Chapter 4 to Canada’s participation in the Community of Democracies (CD). One of our Canadian witnesses, Jeffrey Kopstein argued that, given the UN’s weaknesses and limitations, the CD should be bolstered. In Washington, where we met with Richard Rowson, President of the CD’s Council, Theodore Piccone, Director of the Democracy Coalition Project (and representative of the Club of Madrid in Washington) argued that “Canada should be a member of the [CD] Convening Group,” and that notwithstanding our multi-lateralist reputation, Canada “has been mostly at the margins in this regard.”

Others were less convinced of the CD’s effectiveness. Richard Haas, President of the Council on Foreign Relations, told the Committee that the CD defines its democracy membership criteria too broadly and is too large to be a meaningful actor. Thomas Melia, Deputy Director of Freedom House told the Committee in Washington that the Convening Group of the CD represents in part the strategic interests of the member governments. For example, Morocco is a member although it does not meet the democracy criteria. Mr. Melia also had some cautionary words on trying for global coordination, stating that “a lot of effort can be diverted into coordination.” Instead he saw the need for “complementarity,” and “the way to pursue that is to build one’s niche.”

Gareth Evans, President of the International Crisis Group, has also cautioned:

Don’t pin too many hopes on Democracy Caucuses and similar grand international strategies. While in principle an attractive idea, there are simply too many institutional and interest differences between democratic countries for a united front to be sustained on anything very much, and it is not at all clear that the tentative moves to create such mechanisms have so far placed any useful pressure on non-democracies, or generated any net positive returns.

At the same time, Mr. Evans, who remains a strong believer in a strengthened and reformed UN system, points out that individual democratic countries, notably those with great-power interests such as the U.S., are often not the best placed to promote democratic development. Even if, as several U.S. witnesses told the Committee, Canada is sometimes able to do things that the U.S. cannot, Canada cannot go it alone in this field either. Mr. Evans argues that: “One way to have an impact without such visible badging [association with Western big-power interests] is working through collaboration with multilateral coordinating mechanisms in the UN and elsewhere — the new UN Democracy Fund now getting off the ground will hopefully prove of real utility in this respect.”

The Committee shares that hope. Indeed, there is no substitute for action by the UN, for all its faults, since it is the only truly global body. We, too, want to see it reformed and made into a more credible instrument for advancing democratic development. With respect to the UN Democracy Fund (UNDEF) set up as a result of the September 2005 UN Summit, it is supported through voluntary donations not assessed contributions. The largest donor by far is the U.S., and the second largest donor has been India, the world’s most populous democracy, with a contribution of US$10 million. That amount was matched by Japan in early March 2007, adding to UNDEF’s funding capacity of about US$ 65 million, and making it the Fund’s 28th donor country. So far Canada is not among these.

When the Committee met with UNDEF representatives, Acting Executive Director Magdy Martinez-Soliman and Senior programme Officer Randi Davis (a Canadian) in New York in February 2007, Mr. Martinez-Soliman observed that the Fund is the first UN organization to use the word “democracy” in its title.377 Moreover, parliaments have been one of the better allies of the new fund; UNDEF staff having met with delegations from India, the United Kingdom, the European Union, the United States and others, now including Canada. The visit of the Committee was prominently noted on UNDEF’s web site (http://www.un.org/democracyfund/). It was made clear to the Committee that Canada’s involvement would be welcomed, especially as Canada’s democracy is looked upon favourably by many countries in the world.

The idea for UNDEF was explained as a U.S. initiative proposed as part of the UN reform debate along with priorities such as human rights, management reform and a Peacebuilding Commission. (The Committee also met separately with Canadian Carolyn McAskie, UN Assistant Secretary-General in charge of the Peacebuilding Support Office.379) UNDEF currently works mostly through civil society organizations as well as partnerships with other UN organizations, including peacekeeping missions. Its first funding tranche in August 2006 involved some 70 NGOs, including in Canada the Parliamentary Centre and a journalists group in Toronto. Importantly, UNDEF funding also comes from the South; it is not in the “import-export” business in terms of democracy, and does not offer a democratic model for others to copy. Significantly, too, UNDEF does not require host government permission when it decides on funding projects. It operates with the support and legitimization of the Secretary-General and the states that make up its board, composed of the six largest contributors. UNDEF is also one of the earliest examples of the “One UN” model proposed by the report of a recent High Level UN Panel on Coherence, Delivering as One,380 that was also referred to in the Committee’s meeting at the UNDP.

UNDEF is still a fledgling organization with only six staff (as of February 2007), and has just starting work on the ground, although it already has some 125 projects in 110 states and territories. Its regional priority is Africa (37% of project funding), followed by least developed countries outside of Africa. Project decisions are made on the basis of detailed proposals after consultation with the UN’s Department of Political Affairs and other UN organizations active in each country, following which a short list is made and presented to the board, which makes an even shorter list for presentation to the Secretary-General. With no formal advertising, UNDEF received over 1,300 applications in its first two weeks of operation — although about 700 of these did not meet its criteria. (Even when UNDEF did not fund projects, however, it has shared its database of proposals with other UN bodies, so these projects may get funding from elsewhere.)

The UNDEF governance structure is bi-level: one composed of UN member states, and one of NGOs, respecting geographic balance, and with an advisory board that includes international democracy experts such as Guillermo O’Donnell cited by the Committee in Chapter 1. Asked why UNDEF has accepted funding from states such as Qatar that are not fully democratic, Mr. Martinez-Soliman responded that UNDEF does not judge the degree to which its donors are democratic, but poses the larger questions of: Do the citizens within a state think it is democratic, and do other states think so?

Mr. Martinez-Soliman added that UNDEF has about 15 projects that work directly with political parties in countries such as Bolivia, Serbia and Peru. There are obviously sensitivities involved in such work. Observing that some countries have tightened their legislation on the transfer of foreign money to NGOs, in order to prevent these countries from shutting the door, UNDEF specifies that NGOs must be recognized either nationally or internationally. UNDEF also works in partnership with global and regional interparliamentary forums — for example, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), particularly on the issue of support for increasing the number of women parliamentarians, and including the Assemblée parlementaire de la francophonie.

The Committee was told, by our Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations John McNee, that Canada’s official position on UNDEF remains one of “wait and see.” We agree that UNDEF is a work in progress. But at the same time, it is part of UN reform and a global UN effort to take democratic development seriously. Surely that goal merits Canadian support. We note as well that among UNDEF’s donors are five of Canada’s G7 partners and its Commonwealth partner, Australia. Accordingly, we believe that Canada should consider whether to become a UNDEF donor.

Finally, there is a recurring theme that has struck the Committee during its meetings with international organizations supported by Canada that are involved in democratic development: namely, the impressive number of Canadians who are working in these organizations, often at senior levels. This is a great pool of expertise and experience upon which to draw. While some of these Canadians may be attracted back to Canada by the new Canada foundation for international democratic development that we proposed in Recommendation 12, it is also a good to have Canadians in positions of influence inside the multilateral organizations that Canada funds.

The Committee believes that a greater effort should be made to tap into the knowledge accumulated by Canadians working in multilateral organizations. This could enrich Canada’s own approach to democratic development as it is elaborated through an enlarged Democracy Council and through the independent Canada foundation that we have proposed.

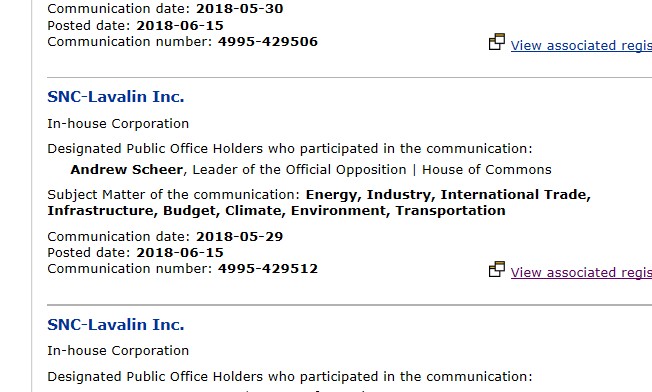

The Foreign Affairs Committee of Stephen Harper’s Government also approved the idea of participating in a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly in July 2007. It seems that all of these successive administrations are globalists.

8. Recommendations From 2007 Report

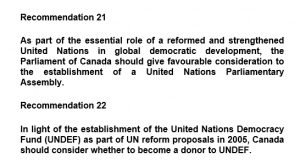

Recommendation 19

The independent evaluation of all Canadian support for democratic development that we have recommended should also assess the effectiveness of multilateral channels to which Canada provides funding. That evaluation should guide appropriate funding levels.

Recommendation 20

Recognizing that the future challenges of democratization processes involve governance at the level of international organizations, as well as in national and local settings, the Canada foundation for international democratic development should include these dimensions within its mandate, and should consider related proposals for support from Canadian non-governmental bodies and civil-society groups working in this area.

Recommendation 21

As part of the essential role of a reformed and strengthened United Nations in global democratic development, the Parliament of Canada should give favourable consideration to the establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly.

Recommendation 22

In light of the establishment of the United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF) as part of UN reform proposals in 2005, Canada should consider whether to become a donor to UNDEF.

Recommendation 23

Taking into account the expertise and experience on democratic development that has been accumulated by Canadians working in this field through multilateral organizations, Canada should make an effort to tap into this pool of knowledge in furthering its own approach to democratic development.

Exactly what it sounds like: create and participate in a United Nations Parliament.

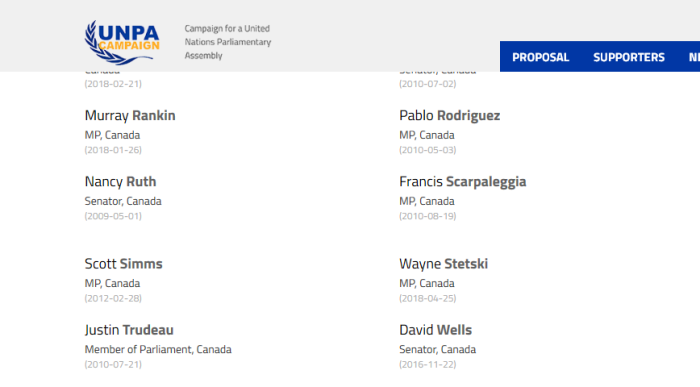

9. Trudeau Endorses UN Parliament

Our current Prime Minister endorsed the concept back in 2010. It seems doubtful that he has changed his mind since.

Interestingly, Green Party leader Elizabeth May (who also sits on the Trudeau Foundation) has endorsed this as well.

10. CDA Globalist Gov’ts All In Support

Successive Canadian Governments all support being part of a UN Parliament if it ever became a reality. Canada is pretty screwed.