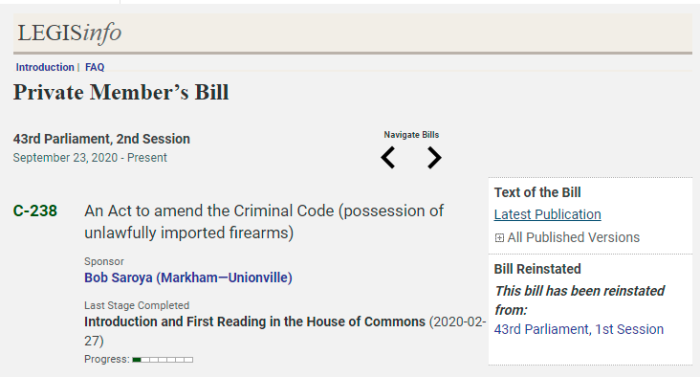

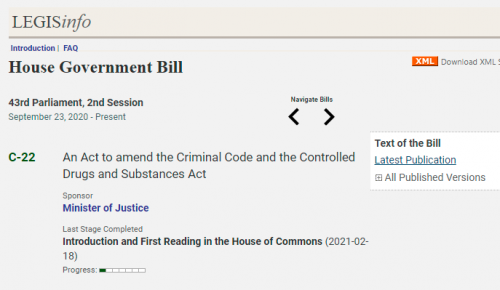

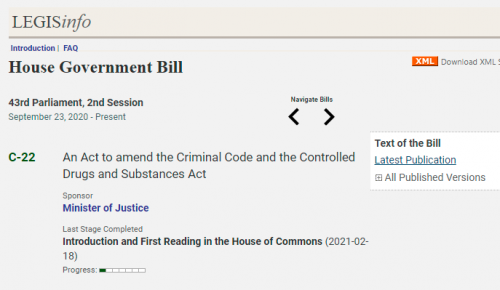

The other day, Bill C-21 was introduced, which would bring “red-flag” laws into Canada, and make it easier to seize guns. Now, we have Bill C-22, which reduces the penalties in the Criminal Code for crimes committed with guns. Keep in mind, last May we had an Order In Council which immediately banned some 1,500 guns.

Who gets targeted? Legal gun owners.

Who gets a break? Criminals who use guns.

1. Gun Rights Are Essential, Need Protecting

The freedoms of a society can be gauged by the laws and attitudes they have towards firearms. Governments, and other groups can push around an unarmed population much easier than those who can defend themselves. It’s not conspiratorial to wonder about those pushing for gun control. In fact, healthy skepticism is needed for a society to function.

2. JT Cut Penalties For Terrorists/Pedos

In 2018, Bill C-75 was addressed. It cut the penalties for terrorism offences. The media didn’t seem to cover that it also lowered the penalties for child sex offences as well. Tt has also been proposed to decriminalize non-disclosure of HIV status for sexual partners. Now, we get to Bill C-22, scrapping mandatory minimum sentences for people committing crimes with guns.

3. Section 85: Firearm Use Offences

85 (1) Every person commits an offence who uses a firearm, whether or not the person causes or means to cause bodily harm to any person as a result of using the firearm,

.

(a) while committing an indictable offence, other than an offence under section 220 (criminal negligence causing death), 236 (manslaughter), 239 (attempted murder), 244 (discharging firearm with intent), 244.2 (discharging firearm — recklessness), 272 (sexual assault with a weapon) or 273 (aggravated sexual assault), subsection 279(1) (kidnapping) or section 279.1 (hostage taking), 344 (robbery) or 346 (extortion);

(b) while attempting to commit an indictable offence; or

(c) during flight after committing or attempting to commit an indictable offence.

Marginal note: Using imitation firearm in commission of offence

(2) Every person commits an offence who uses an imitation firearm

(a) while committing an indictable offence,

(b) while attempting to commit an indictable offence, or

(c) during flight after committing or attempting to commit an indictable offence,

.

whether or not the person causes or means to cause bodily harm to any person as a result of using the imitation firearm.

Marginal note: Punishment

.

(3) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) or (2) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable

(a) in the case of a first offence, except as provided in paragraph (b), to imprisonment for a term not exceeding fourteen years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of one year; and

(b) in the case of a second or subsequent offence, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of three years.

(c) [Repealed, 2008, c. 6, s. 3]

Bill C-22 would change 85(3) to this:

“Punishment

(3) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) or (2) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 14 years.”

No more mandatory minimum prison sentences for the above offences. While a Judge would “likely” still impose one, it’s not required if this Bill passes as is.

4. Section 92: Unauthorized Possession

Possession of firearm knowing its possession is unauthorized

.

92 (1) Subject to subsection (4), every person commits an offence who possesses a prohibited firearm, a restricted firearm or a non-restricted firearm knowing that the person is not the holder of

.

(a) a licence under which the person may possess it; and

(b) in the case of a prohibited firearm or a restricted firearm, a registration certificate for it.

Marginal note: Possession of prohibited weapon, device or ammunition knowing its possession is unauthorized

.

(2) Subject to subsection (4), every person commits an offence who possesses a prohibited weapon, a restricted weapon, a prohibited device, other than a replica firearm, or any prohibited ammunition knowing that the person is not the holder of a licence under which the person may possess it.

Marginal note: Punishment

.

(3) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) or (2) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable

(a) in the case of a first offence, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years;

(b) in the case of a second offence, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of one year; and

(c) in the case of a third or subsequent offence, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of two years less a day.

Bill C-22 would change 92(3) to this:

Punishment

(3) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) or (2) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 10 years.

No more minimum sentences.

5. Section 95: More Illegal Possession

Possession of prohibited or restricted firearm with ammunition

.

95 (1) Subject to subsection (3), every person commits an offence who, in any place, possesses a loaded prohibited firearm or restricted firearm, or an unloaded prohibited firearm or restricted firearm together with readily accessible ammunition that is capable of being discharged in the firearm, without being the holder of

(a) an authorization or a licence under which the person may possess the firearm in that place; and

(b) the registration certificate for the firearm.

Marginal note: Punishment

.

(2) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1)

(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of

(i) in the case of a first offence, three years, and

(ii) in the case of a second or subsequent offence, five years; or

(b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Bill C-22 would change 95(2)(a) to this:

“(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 10 years; or”

Once again, mandatory minimum sentences would disappear.

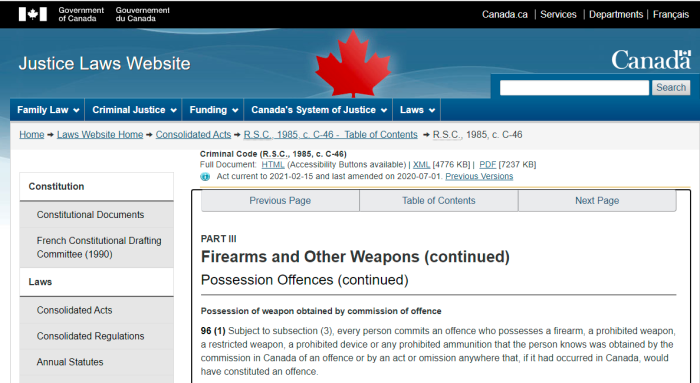

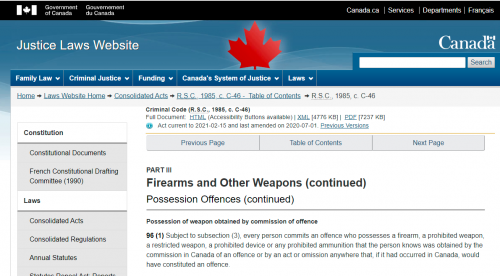

6. Section 96: Firearms Used In Crime

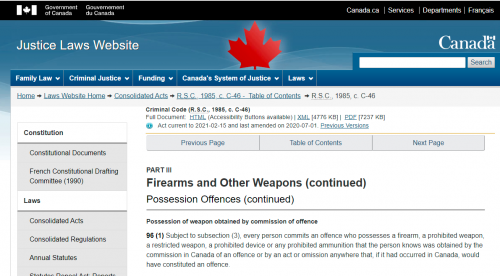

Possession of weapon obtained by commission of offence

.

96 (1) Subject to subsection (3), every person commits an offence who possesses a firearm, a prohibited weapon, a restricted weapon, a prohibited device or any prohibited ammunition that the person knows was obtained by the commission in Canada of an offence or by an act or omission anywhere that, if it had occurred in Canada, would have constituted an offence.

Marginal note: Punishment

.

(2) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1)

(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of one year; or

(b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Bill C-22 would change 96(2)(a) to:

“(a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 10 years; or”

No more mandatory minimum jail sentences.

7. Section 99: Trafficking Guns/Weapons

Weapons trafficking

.

99 (1) Every person commits an offence who

(a) manufactures or transfers, whether or not for consideration, or

(b) offers to do anything referred to in paragraph (a) in respect of

.

a prohibited firearm, a restricted firearm, a non-restricted firearm, a prohibited weapon, a restricted weapon, a prohibited device, any ammunition or any prohibited ammunition knowing that the person is not authorized to do so under the Firearms Act or any other Act of Parliament or any regulations made under any Act of Parliament.

Marginal note:Punishment — firearm

.

(2) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) when the object in question is a prohibited firearm, a restricted firearm, a non-restricted firearm, a prohibited device, any ammunition or any prohibited ammunition is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of

(a) in the case of a first offence, three years; and

(b) in the case of a second or subsequent offence, five years.

Marginal note: Punishment — other cases

.

(3) In any other case, a person who commits an offence under subsection (1) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of one year.

Bill C-22 would change 99(3) to this:

“In any other case, a person who commits an offence under subsection (1) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 10 years.”

Section 100(3), weapons trafficking, would also be changed such that the required minimum jail sentence would be removed. The Court could still issue them though, but would have discretion.

8. Section 244: Discharging A Firearm W/Intent

Discharging firearm with intent

.

244 (1) Every person commits an offence who discharges a firearm at a person with intent to wound, maim or disfigure, to endanger the life of or to prevent the arrest or detention of any person — whether or not that person is the one at whom the firearm is discharged.

Marginal note: Punishment

.

(2) Every person who commits an offence under subsection (1) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable

(a) if a restricted firearm or prohibited firearm is used in the commission of the offence or if the offence is committed for the benefit of, at the direction of, or in association with, a criminal organization, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of

(i) in the case of a first offence, five years, and

(ii) in the case of a second or subsequent offence, seven years; and

(b) in any other case, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of four years.

Subsequent offences

.

(3) In determining, for the purpose of paragraph (2)(a), whether a convicted person has committed a second or subsequent offence, if the person was earlier convicted of any of the following offences, that offence is to be considered as an earlier offence:

(a) an offence under this section;

(b) an offence under subsection 85(1) or (2) or section 244.2; or

(c) an offence under section 220, 236, 239, 272 or 273, subsection 279(1) or section 279.1, 344 or 346 if a firearm was used in the commission of the offence.

.

However, an earlier offence shall not be taken into account if 10 years have elapsed between the day on which the person was convicted of the earlier offence and the day on which the person was convicted of the offence for which sentence is being imposed, not taking into account any time in custody.

If passed, 244(2)(b) and 244(3)(b) will now each read:

“in any other case, to imprisonment for a term of not more than 14 years.”

Section 344(1)(a.1) and 346(1)(1.a) are also repealed, which would have called for 4 year minimum sentences in some robbery cases and extortion where firearms were not used.

It’s not enough that legal gun owners can be targeted under proposed red flag laws, or that their guns can be outlawed. Now, the Government sees fit to reduce the penalties for those committing crimes with guns.

This isn’t stupidity or ignorance.

It’s war against the Canadian public.

Like this:

Like Loading...